Opera is what Silicon Valley would call a legacy art form, and the Bay Area often seems uncertain how to approach the repertoire of the past (California, we are told, is inventing the future). Staging a one-act about Steve Jobs was one way of admitting defeat in advance, but better-intentioned efforts at topicality can also go awry; for me, I think of the time Peter Sellars tried to give György Kurtág’s Kafka-Fragmente a social conscience by having Dawn Upshaw roll around under an ironing board. Happily, in this respect as others, Oakland is rendering the more established institutions irrelevant. For more than a decade West Edge Opera has been staging weird repertory in train yards and warehouses; this season, following a premiere about Dolores Huerta and a refashioning of the Baroque David and Jonathan as two hunks in love, we finish with a brilliant production of Alban Berg’s Wozzeck in the grand old Masonic auditorium of the Scottish Rite Center.

This modernist monument of an opera was completed in 1922, and the libretto is a century older. Playwright Georg Büchner ranks beside Kafka among the dark sphinxes of German literature; born in Hesse in 1813, he attempted to start a peasant revolution while in medical school but died of typhus at age 23, leaving behind three plays so out of step with their time that they remained unstaged for decades. Woyzeck, his final work, was just manuscript fragments (the variant spelling literally has to do with trouble reading his handwriting) and is sometimes called the first working-class drama in literature, though no proletarian heroics are on offer. The title character is a soldier stationed in a small German town, where he lives with his mistress and illegitimate child, doing odd jobs for extra pay and offering his body for medical experiments. Meanwhile his sanity is fraying. Tormented by hallucinations, he murders his mistress in a jealous fit and drowns while attempting to dispose of the knife. The text is disjointed and surreal, full of abrupt transitions and dreamlike images; like Beckett, it offers formal brilliance and black humor but not a whisper of consolation. It was finally first produced in 1913, to the instant rapture of the expressionist avant-garde. The young Berg knew on first viewing that he wanted to set it to music, and cemented his bond with the protagonist while serving in the Austro-Hungarian army. As he wrote to his wife, “I have been spending these war years just as dependent on people I hate, have been in chains, sick, captive, resigned, in fact humiliated.”

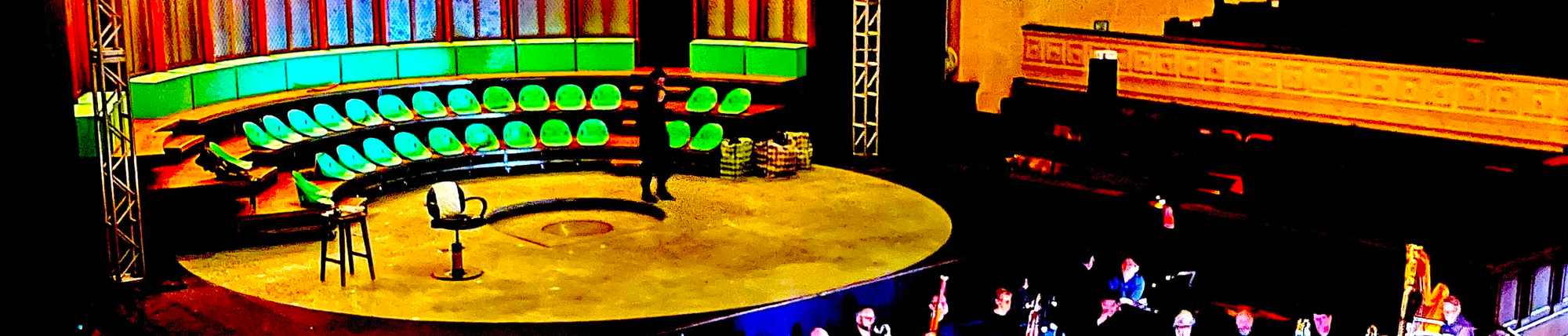

Director Elkhanah Pulitzer calls Wozzeck “a harrowing critique of the systems of power we create that ultimately corrupt and exploit our most vulnerable.” This is quite true; it is also a deeply mysterious piece that defies reduction to a single message. Pulitzer’s production successfully threads the needle, making its statement without flattening out the strangeness. The Scottish Rite Center is a much smaller house than the War Memorial across the bay, where San Francisco Opera puts on its shows; stepping inside, you find yourself surprisingly near the stage. Pulitzer has conceived the set as a brutalist arena centered on a metal drain, backed by tiers of seats in a sickly hospital green. It feels as though the concrete substrate of Oakland has followed you inside the venue, all the more when you realize that someone is already on stage, blankly shuffling among the seats like a displaced figure from the sidewalk outside. Is he supposed to be up there? You might have to check your program before you recognize baritone Hadleigh Adams, in character as Wozzeck and already lost.

From the first notes, it’s clear Wozzeck never had a chance. Tasked to shave his regimental captain, he meekly absorbs a lecture on the immorality of having a child out of wedlock (sung with manic energy by Spencer Hamlin). In response he pleads poverty, but right away has to take far worse from his other employer: the local doctor, portrayed by bass-baritone Philip Skinner as a terrifying dom in sunglasses and a leather harness. Orderlies drench Wozzeck with buckets of water as the doctor scuttles around on a rolling chair, rebukes his patient for urinating (“Haven’t I proved that the bladder is subject to the will?”) and orders his diet restricted to beans. Wozzeck’s hallucinations delight him, so he tosses his guinea pig a few pennies: “You’re an interesting case, Wozzeck, just keep behaving.”

The mystery of the opera is that Wozzeck is interesting. When not offering excuses or hangdog apologies, he speaks in visionary fragments defying summary: “Do you see the bright streak over the grass, where the toadstools grow? At dusk, a head rolls around there. Someone picked it up, he thought it was a hedgehog.” No cheer in these lines, but there is strange beauty. Berg’s score retains the outlines of traditional operatic form but avoids the cadences of tonal music, leaving the listener suspended in a universe without a key center. The orchestra, playing under the direction of Jonathan Khuner, marvelously outlines both the harsher and gentler moments, while Hadleigh performs his part largely in Sprechstimme, a modernist vocal technique that fudges pitch to suggest the speaking voice.

In a world so off kilter, Wozzeck sees more deeply into the truth of things than the supposedly sane characters. But it is impossible to sentimentalize him. Even before Wozzeck’s relations with his mistress Marie turn homicidal, they are empty of tenderness. He raves to her about lights in the sky and quotes Scripture: “The smoke of the country went up as the smoke of a furnace.” The audience might catch the reference to Sodom and Gomorrah under airstrike, but all Marie can see is that Wozzeck won’t look at his own child. Emma McNairy inhabits the role with tragic grandeur; her liaison with a braggart drum major is no more high-minded than anything else on stage, but her love for her child is real, and allows her to stand as Wozzeck’s opposite number until she becomes his victim.

During intermission, while the rest of the cast retreats, Wozzeck is forced to remain on view, changing out of his soaked clothes and wiping up spills. More than an ornament, the central drain turns out to be a working fixture, which swallows all the opera’s runoff—water, beer, liquor, piss, blood—and bends the characters to its gravity. They circle around it constantly, sometimes in pursuit of love or vengeance, sometimes in play (Marie and her child make anachronistic airplane wings together) or, as in Wozzeck’s shuffling gait, out of mindless compulsion. A centripetal curve also guides the plot, which starts as a sequence of fragments but soon tightens toward destruction. Betrayal, discovery and vengeance follow on each other with sickening speed; inevitably, the last bit of waste to disappear down the drain is the protagonist himself. The opera’s famous last line—“Hop, hop” on a descending fourth—goes to Marie’s orphaned child, who circles the arena in a lonely reprise of the airplane game. It’s a heartbreaking last glimpse of the reduced state that Giorgio Agamben called bare life.

After curtain call we step back into an ordinary afternoon on Lakeside: sun on the water, bicycles and PA speakers. No pat sentiments go with us; the show has avoided cheap gesture. But the central drain, that inhuman infrastructure meant to dispose of anything considered a waste product, might return to us when a walk through West Oakland is cut short by the I-980 barrier, or when the city chooses to make an encampment disappear. Germany in the nineteenth century and Austria in the twentieth had their interpretations of how we ought to treat our most vulnerable, and history has entered them into its record. Oakland in 2025 is next on the list.

–Pauline Kerschen