I was only a few pages in but Cassandra at the Wedding got right to it: “The bridge looked good again.” I underlined it immediately; I knew exactly what she meant. I hadn’t realized it would be that sort of narrator. (You know the kind). Further on, she’s slightly more sardonic: “I am not, at heart, a jumper…it’s just not my sort of thing.” The implication, of course, being: but maybe. Always, unfortunately: maybe.

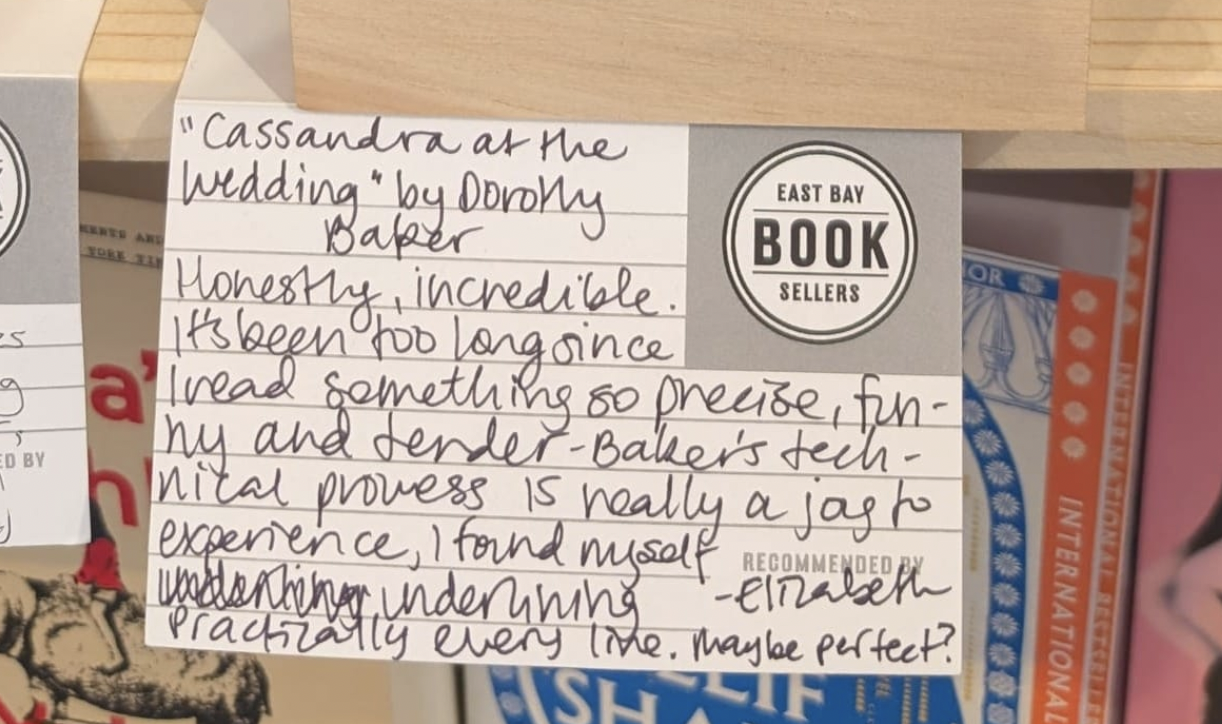

We meet Cassandra as she prepares to leave Berkeley and drive towards the Sierra Nevadas to her family ranch, where her twin sister will be married. Maybe. I read it in nearly one sitting, jotted a few lines on a staff recommendation card at work, stuck it on display, and went about my life. Customers asking what I had read recently got a copy handed to them along with the assurance that this was a funny, beautiful book. I mostly neglected to tell them it is, by and large, about suicide. I think I forgot.

Here’s something I remember: When I was 17 and had moved to San Francisco for my first year of college, I began walking at night. Miles and miles, for hours at a time, if one was keeping track. I was not keeping track. As soon as my roommates and the person I was dating and the rest of the world were asleep, I would put on my headphones, make my way out of our on-campus apartment, resist the urge to fully take off running and instead opt for chain smoking and walking so fast it felt like flight. Around the baseball field, circling circling circling, until I couldn’t take the repetition, and then head out down 19th Avenue and into the stillness of suburban San Francisco. I wouldn’t, couldn’t stop.

It was very quiet and I never saw anyone else, barely any cars. Sometimes I would cry in a way that felt good, like letting off pressure. I often didn’t notice until the wind hit the wet sheen on my face. Miles and miles and miles.

Cassandra makes her way east, drinking perhaps a bit too much at roadside bars as she goes. I fear for her safety. Her sister asks her over the pay phone whether she’s eaten dinner, and she says she has, but notes to herself that she “can’t remember ever having eaten.” Shortly after, she refers to having ”gotten out of the habit” of eating, a line I emphasize with more urgency than needs to be discussed. My worry is not misplaced, she’s just getting drunk, not crashing cars or getting preyed upon or whatever. And the idea of a drink or two as you make your way along an old highway appeals to me very much, although I’m well enough, now, to recognize it as a bad idea rather than an economical use of time. But who am I to judge? Let the girl have a few.

Cassandra arrives at her destination (which I envision somewhere between the house from a Parent Trap movie and those labels they made in the ’30s to promote fruit), where it is evident that drunkenness (whether driving or not) does not raise alarm. Her father has a permanent glass of cognac and offers a cold beverage at any hint of emotion. But it’s the 1960s. It’s very hot outside. When we are ensconced in this house, and in this family, we too begin to unwind. And wouldn’t a drink be nice? After all, why not?

The family pool doesn’t have a shallow end. They wanted it that way. High school swim competitions, ribbons on the wall, 9 feet deep at the drain: Cassandra is in her element, she says. Submerging the body in water solves many, many problems. The longer we stay down, the more our brain can relax. Emerging for air, she sees Judith at the edge: “‘I thought you weren’t ever going to come up,’ she said, and I told her it was a sort of last-minute decision.” Offered a comb for her hair (there was no cap and “bats get in your hair”), she threw it at an embankment. Returning with a whalebone bristle brush, belonging to their late mother, Judith runs it through her twin sister’s hair (“scalping me” in “tearing jerks”), in the quiet dark under constellations they can both map and name. More Hennessy is poured and drunk, and one glass is deliberately shattered poolside. Cassandra bleeds only a little bit. She has the fortitude to berate her sister’s reasonable concerns.

It can be good to shock our families. It can help us remember who we are. But I think the twist of the knife is that Judith isn’t troubled enough. Either this is so typical of her twin that it doesn’t register as alarming, or it is outside of the family system’s capacity to call it what it is and shake it awake. Which is worse? Impossible to say.

Waking up violently hungover the next morning, Cassandra makes herself a mixture of raw egg, orange juice, and vodka. Her grandmother is busy with her own breakfast: French toast, bacon, eggs, none of which Cassandra will eat. They talk wedding gifts. Her grandmother offers to buy something and let her granddaughter sign it off as hers; Cassandra offers, instead, an obvious lie about having bought the couple “stainless…spotless, immaculate stainless,” refusing to elaborate. Judith is nowhere to be found.

My own grandmother—who was deeper in the throes of dementia than we knew at the time—once pulled me aside to visit her studio. This was a room I had barely seen in the decades of my life I’d been visiting that house. There were drawings and canvases everywhere, mostly figure studies and portraits, beautiful confident lines and textures, piles of them. I knew she had always taken art classes and I knew she worked up here, but that day she told me something I didn’t know, but which, possibly, should have been obvious: Sometimes she works through the night. Sometimes she can’t stop. Sometimes she thinks that all she wants to do all day long is paint and paint and paint and paint. Sometimes it’s very scary but it’s often a little bit fun. Sometimes two emotions can blend and form something different, a new color. We looked at one another, through a gulf of experience and age and unspoken family secrets and pain, and we maintained the vine of silence that chokes family trees. But I almost, almost asked her: Did you ever go on walks? Ever see a bridge?

Shortly after the events of breakfast we find the absent twin. This section is entitled “JUDITH SPEAKS” although “let’s get the well adjusted one in here” would also work. I initially thought I loved being in her brain, getting her calm perspective, but as I read on I realized I was actually feeling something like shame: Here’s Judith, with her own problems, her own life, for god’s sake her own wedding. And yet Cassandra is sucking all the air out of the weekend, screaming for help and lashing out when it is offered. And here I am, drinking down this book, deciding it’s an image of myself reflecting back, obviously so eager to receive recognition or validation or something that I forget this is not actually my story.

It’s easier to assume everyone can relate, is having the same sort of time we are, or at least has docked their ship in these ports, if only briefly. I believe that is referred to as projection, professionally speaking. Is that what plagued Cassandra? Difficult to say if it was my particular ailment, either. But for many years I convinced myself that my life was not impaired or disrupted. It was simply my life. It’s easier to admit nothing, to cover the vodka label as you pour it into your breakfast drink, calling it “white port wine,” which is recommended for general health, blood cell counts, and the soothing of one’s pyloric valve (and then rearrange all the empties in the pantry). Sure, Cassandra, valve health. It’s easier not to reveal your secrets, easier to deflect from them. “I’ve never felt badly in my life,” Cassandra tells her grandmother, while pouring her furtive breakfast concoction. “No matter how sick I am, I always feel well, at least.”

After I had sent a few customers home with Cassandra, I started to feel a bit uneasy. Should I be warning them? Am I obligated to tell adults to brace themselves? Isn’t everyone a little bit mentally ill? Call of the void, that’s a thing we all have, right?

I know the answers to most of these questions but still, they persist. Even now, a light panic: Why am I telling my secrets here, in the tacit admissions which come along with a recommendation? When a customer asks what I’ve read, I’m not under oath to answer truthfully. Besides, don’t they want to think about themselves, instead of about me? Don’t they want something simpler, something well? Surely not all this jumping and not eating and never wanting to come up for air, all this symbology of bridges.

I’m not sure. I tell myself: If anyone even reads the books I recommended, they will probably think about their own lives: their families, their dramas, perhaps their weddings. Perhaps their own bridge sightings. They will project. As they should.

I walked too much in San Francisco, but I don’t walk like that in Oakland. I like to go down to the corner store by my house for a bottle of mineral water and to see the white cat that sleeps there. When the weather is right and the mood strikes me, I hike up the gradual hill of Claremont Avenue. On my lunch breaks, I watch as the houses get bigger, the redwoods break apart the sidewalks, and suddenly you’re in Berkeley. There is a park where you can see all of Oakland’s port, all the bridges, the hills of the city, the headlands. All of it looks good, but not, you know, Like That. You can stroll in that park at sunset, you can get a sandwich at the market nearby. After my car’s ignition got ripped out twice in two months, I would often go to a small brewery on San Pablo, then walk home in the waning twilight and take pictures of the shadows on all the plants.

If someone asked me, a trusted regular customer, maybe, I would say that these days I am gentle in my body, curious about who I am and what I feel. I am not interested in bringing about my own death. And yet! A little sliver of my brain often wants me to add: but maybe. So, okay. I don’t believe it, and I won’t allow it. But maybe. I would say, to that trusted customer, that part is the same exhausting part that Cassandra and I share, that it makes us need so many things, most of all attention and care. Perhaps that’s the selfish part that can’t abide being ignored because it feels so close to oblivion, the part that can’t just read a book and move on but has to press it into people’s hands and then have the gall to wonder what all of that says about me. I would say to them: I’ve learned about box breathing, about letting thoughts float past without judgment, about going at a normal pace and trusting that I will not combust. I’ve learned to touch my hand to my chest and name what I feel: certainly a little tired, maybe hungry, probably needing a glass of water. I would say I have learned, finally, to care.

I might even say, there’s this line from a poem I love. The poem is called “Trouble,” by Matthew Dickman, and I have loved it for a long, long time, so much so that it lives in a frame in my house. There was that year or two when I needed it on the wall right next to my face when I woke up, taped in a corner I covered with photos, pressed flowers, postcards, all pieces of who I wanted to become and reminders of who I had been. Most of those artifacts have been tucked away or lost but “Trouble” has found its way into a more permanent and protected place.

I don’t need it next to my bed anymore. These days, I like waking up and looking at the quart jar of water, the lip balm and the stack of books on my nightstand. I like feeling better than I used to feel. The line at the end of that poem goes something like “I want to be good to myself.” And I want to try.

But no one has asked. I doubt that they will.

Yesterday afternoon while I was out walking, I noticed a hole in the pavement on the sidewalk. It was small, made with precision and deep enough not to see where or if it ended. I kept going, didn’t drop to my knees or attempt to liquefy or anything. But I did wonder what would happen if I went inside.