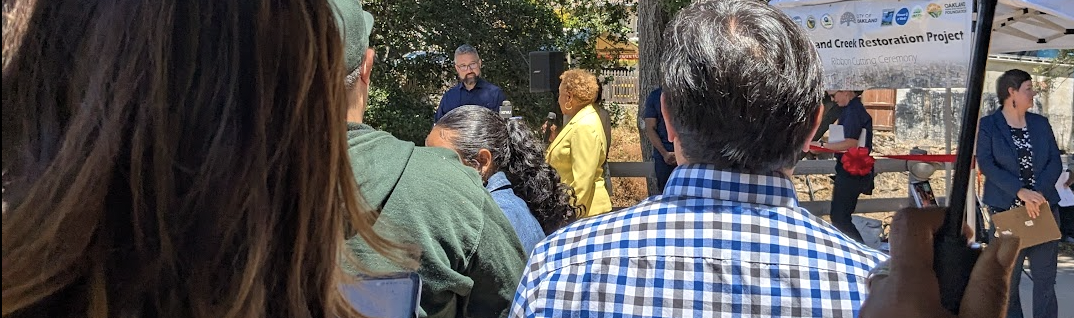

The sun is out and so is Barbara Lee, both very bright and yellow-suited. A violinist wails on her amplified and very jazzy electric violin as Courtland Creek breathes behind her, between Brookdale and Fairfax Avenues.

We build cities along rivers, and then build over them, to steal a phrase from Robert Macfarlane. Most of Courtland Creek is crushed and culverted, like most of Oakland’s creeks, visible only when floodwaters find their lost beds and resurrect themselves through basement walls.

People mill about the staked oak saplings, in the shade of a towering retaining wall. They all know each other, whether from the neighborhood or intersecting bureaucracies.

One man, to another, “You're here representing CalTrans: you should go represent!" Two women: “Hi Rich! How are you doing?” “Hi Rick!” (Rich/Rick to both: “Tell me your name again?”) Later: “He remarried, got a very young wife.” A set of neighbors, chatting, “Two ladies here came from out of the neighborhood. They’re standing over there in the shade. I wonder if they're creek people.”

They are probably Creek People. Sausal Creek people, to be exact, two watersheds west, who have daylighted a mile of their creek in Dimond Canyon and now tend it as volunteers, ripping out ivy and trying to get native plants growing and rainbow trout thriving. It’s been a few decades. There’s still a lot of ivy, still not so many fish.

Here at Courtland Creek, plugs of yarrow are growing, and poppies, a riparian set of sapling trees. A few old and towering oaks. A monarch settles in to nectar on the flowering towers of a young buckeye planted in the steep banks, orange on pink.

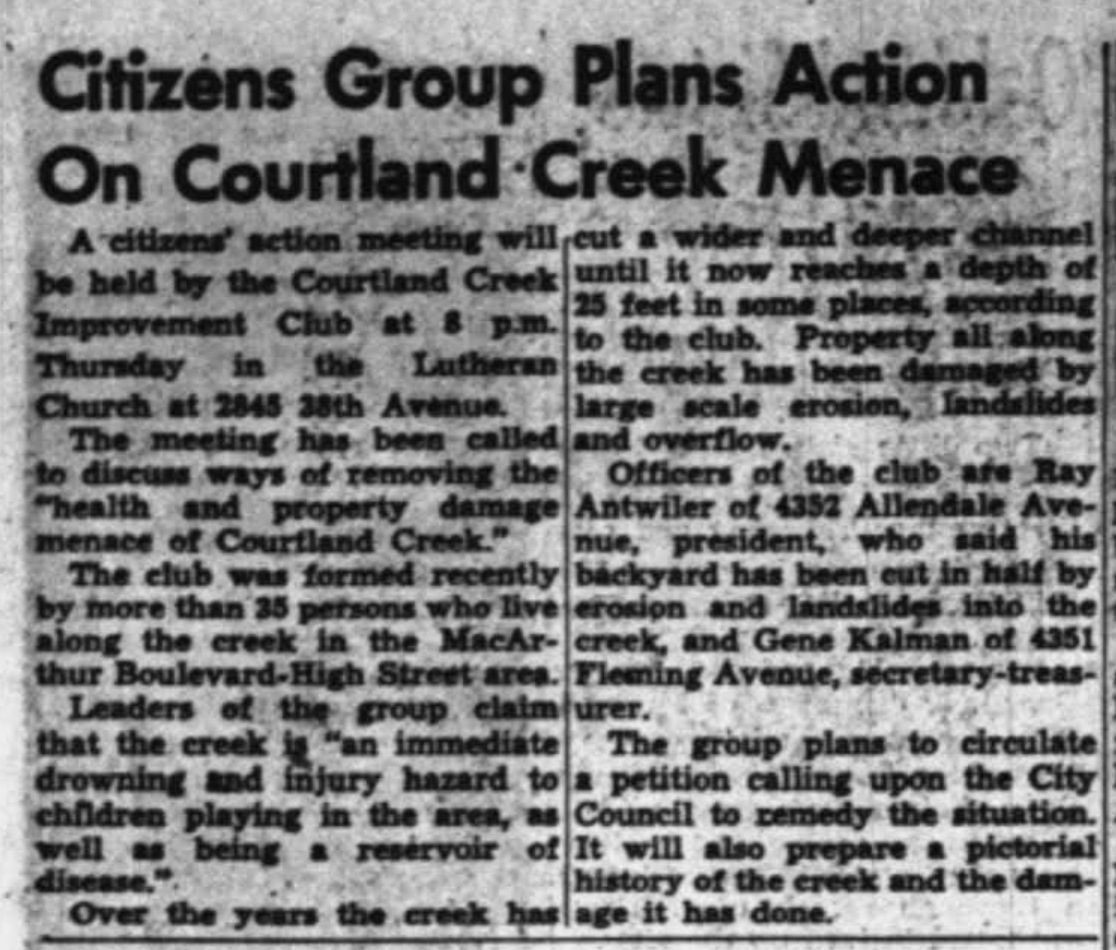

Later I daylight some old Oakland Tribunes. In 1953, the creek was a ”menace,” and decades before these neighbors became Creek People, the folks who lived in these homes had created a Courtland Creek Improvement Club, declaring it a drowning hazard, a reservoir of disease, and blaming it for eroding their backyards that were built onto its banks. One of the leaders was Ray Antwiler, born in Oakland in 1900, whose house two blocks up from the now-park was built in 1939. He was furious, 15 years later, that water beats rock. That house sold this year for $835k: at least it was a Property Value Improvement Club.

Andrew Alden writes that this region of Oakland is geologically confusing, that the constant shimmies of the Hayward fault keep juggling the creeks around into different canyons. Engineers do geology in triple time.

Flood control measures in the middle of last century kept reflowing the creek for local convenience. When the Coliseum was built in the 1960s, engineers cut and cemented channels to keep Courtland Creek and Seminary Creek from spreading out south into a slough along the Bay as it met Lion Creek and the rushy, brackish marshland. Filled in the marsh, built the stadium where I watched Rickey play.

On a satellite image of Oakland, intermittent rivers of green run downhill through the city, all the trees shading the creeks that are still allowed to wash their feet. We’ve had enough rain the last few winters that there’s still a flow between the rocks, but it’s too hot for June, and suddenly the head cop with all the bars on his shoulder is kneeling next to a woman flat out under the speaker’s tent, behind the red ribbon that should be getting cut right about now.

But the woman down is not the mayor, so the show will go on. Somebody steps in: “We're moving the celebration, emergency services needs access.” Much confusion. Are we supposed to clear the path where all the chairs are? Or the shaded area where all the people are? The Woman Down is the main organizer of the whole ribbon cutting extravaganza. She sits up, gets loaded onto a stretcher, waves a queen’s wave to everyone, who applaud.

The violinist who had stilled her bow out of respect starts up again, now with a disco beat behind her.

A City Council member in a blue suit: “I went to my daughter's preschool event, that's why I'm dressed up. I don't even recognize myself!” I am handed flyers from Brookdale Rec Center’s red wagon, asked if I have kids and how old they are. Five and nine. “Oh my God, we want them!”

Barbara Lee, in yellow, in front of the red ribbon: “This is what progress looks like. This was once a dumping ground, now it's a place for families, nature. Folks here know: it did not happen overnight!” It’s been almost forty years, says the new sign.

This creek waters one of the first areas Europeans settled in the entire Oakland region because water was a blessing, before it was a menace, before it was buried.

The Tribune published a 1955 city ordinance announcing budgetary allocation of $115,000 for “engineering, inspection, and incidental expenses” to relocate a stretch of Courtland Creek two blocks west of its geologically determined flow, from 12th & 48th to 14th & 46th, and reduce flooding. There is a department of the Alameda County Government called “flood control,” which is still, most of the time, the main concern of governments when it comes to creeks: we just can’t reconcile ourselves to the California winter that unfurls water hard and fast, scoring and tearing, trying to create marshes, beaches, dunes if we’ll let it.

In 2002, Oakland allotted about half a million in Measure DD for restoration work on 750 feet of this particular creek, which adjusted for inflation, comes to about $35,000 in 1955 dollars. The Stewards, the neighborhood Creek People, lined up grants from regional, county, and state sources to fund the rest of the work. That’s why there are so many people wearing so many differently labeled polo shirts here.

The vibe is a neighborhood block party, with city employees, even if the violin is attempting to change the tone to “fancy wedding.” That guy from CalTrans, and someone from Lateefah Simon’s office, they’re here. John Bliss is here, author of measure Q. Noel Gallo, rep for district 5: “I know most of you who are here.” City Parks Department guys are here; the neighbors know them, shake hands. A bearded white man is here, eating a salad out of a mason jar that’s insulated in a long brown woollen sock. He’s in an Oakland Proud hat (green) and an Oakland City shirt (green). Probably Creek People.

At the end of the nineteenth century, a rail line went through this reclaimed park; when it got ripped out mid-twentieth century, this strip of land, the neighbors say, got treated like a trash place, leftover in the flats of East Oakland, dumped on and in.

A helicopter comes overhead, just as someone who hasn't learned to eat a mic if you want to get heard tries to talk over the whomp-whomp-whomp of the blades, and fails.

“Is there anybody unhappy here today?” A tall man asks. “Nobody comes to a ribbon cutting in a park and is unhappy. So let that be a lesson to you: more ribbon cuttings in parks.”

“Much poetry has been written about creeks and rivers,” begins a Creek Person. She does not follow this by reciting any poems. She does say: “Every day I’m here, I see kids down in the creek, and that's exactly what we want.” A park was a vacant lot, was a railroad line, was a creek, is a creek, is water and rock moving, is Deep East Oakland putting plants in the ground and feet in the flow.

The final speech comes, after many speeches, many thank yous, many names called out in camaraderie among those who have government pensions. It’s given by a Creek Person from the Courtland Creek Stewards: “Get involved in your neighborhood council, that's the only way to get things done.” For better (Stewards), or worse (Improvementers), that has the ring of truth.

She continues, hopeful on an unseasonably warm Bay Area June day: “We need to share our resources, both knowledge and money.... Now people who maybe can't make it up to the redwoods can still be a part of their local creek system.”

“Let's be a community together.”

As the violinist goes to town for one last spate, pizza and waters are handed out, and this is what community does together. A community trying to fix what was done fifty, seventy five, a hundred and thirty years ago, sounds like this: Come here, I want you to meet someone. I’m gonna head home for lunch. One two three, say Courtland Creek! (Gesturing to the violinist) She's good on that! Alejandro – yeah yeah yeah! – how are you doing? No trash cans anywhere? Hang on, I want to take a picture with the violinist.

A dad, on his phone: Hey Paula! We're down at the creek!

–Marthine Satris