Since I unofficially tour the Laurel every day, usually with our dogs, I jumped at the chance when I saw the Oakland Heritage Alliance was leading a history walking tour here. My skeptical seven-year-old is a good sport, swayed by learning that our Goodwill was once a fancy theater and excited that they could bring their notepad. I assure them that the tour’s proximity to home would allow an easy escape if necessary.

We walk together over to the Laurel Art Garden, a leftover sliver from the construction of the 580 freeway that’s been rehabilitated by the Laurel Village Association, now adorned with native plants and a few donated benches. A chain-link fence gestures at defending the park from the freeway, doubling as a gallery wall of locally-sourced painted hubcaps. Two fresh stumps mark the recent absence of a little free library, pointlessly sawed down [by parties unknown] the week before. A caretaker explains that it’ll be resurrected soon. An act of love for a troubled place, the park is Oakland at its best, in my mind.

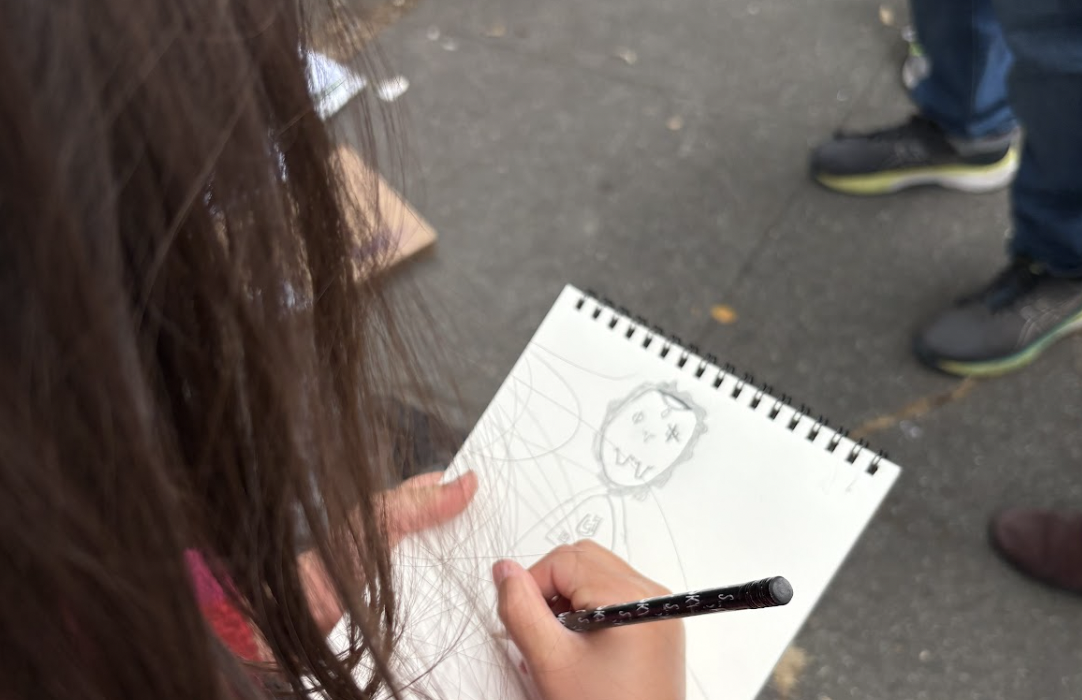

Four OPD squad cars ring a white van a few yards from the meet up spot, which is a bit concerning, but we step past to join about fifty residents, history buffs, and local podcasters (#spotted) and check in with the volunteers. The crowd is notably older and whiter than the neighborhood. As we wait for stragglers, the kiddo is happy to sit on the curb to work on their drawing of an octopus. (I google reference images to help).

Our guide announces himself: Dennis Evanosky, a Laurel resident who published a book on the neighborhood’s history. We follow his lead up 35th, stopping every few blocks and huddling close, as Dennis’s voice amplifies through the speaker worn around his neck. The kiddo perks up at the story of the Ohlone guarding their paint supply—the hematite quarry near Holy Names University (RIP)—and tries to write it all down in their notebook. (Later I find Dennis’s comment on Andrew Alden’s geology blog to fill in the gaps).

Dennis’s history moves on to the Peralta land grant and its borders, transitioning to the influx of loggers, as failed forty-niners extracted ancient redwoods instead of gold. We are losing the kid’s interest here; a snack helps, but the outing may have been overly ambitious. “Are we going to just be listening the whole time?”

A theme is emerging: every stop covers yet another chapter of what the Laurel once was, each absence leaving ripples of grief in their wake. The felled redwoods. The Hilltop Tavern (the native-owned bar in Oakland that hosted the planning sessions for the 1969 Alcatraz takeover). The crooked end of 38th Street, meant for a Key Route streetcar turnabout. Particularly striking are all the shuttered movie theaters, whose ruins are most obvious, and whose glamor is hard to square with the Laurel’s sleepy today. Christened by burlesque icon Sally Rand, the Hopkins Theatre had its first film delivered by blimp; after some time as a Hollywood Video, it’s now a Goodwill and an AutoZone.

Meanwhile, the Laurel Theatre gave way to a dialysis center sitting on a half block of vacant retail space, which Dennis had fought at the time.

Dennis reports having seen the theatre’s old neon sign in its basement before the building was torn down, but it has since disappeared. Later I write to Jim at Neon Works to ask if he’s ever seen it, but no dice. The mystery seems too neat an analogy for the energetic night life that’s also gone missing.

As much as I appreciate being in a group of folks that believe our neighborhood worthy of attention, the walking tour’s format makes me a little uneasy, this roving audience of mostly white folks (myself included) in a neighborhood that is mostly not. Despite best efforts, there are minor frictions, like the mother forced to wheel her stroller into the street to navigate around us. In front of Laurel Elementary, a neighbor rolls his boombox by, as usual, and I note the annoyance as his and Dennis’s speakers compete. The tour interrupts the flow of things. And though it’s tolerated, I can imagine if the roles were reversed, if a young and diverse crowd were roaming through a hills neighborhood, telling their version of its history. Not a bad idea.

Halfway through the tour, the kiddo’s out of patience and I’m out of snacks. But as promised, the landscape’s been layered with stories, footnotes for future walks, and prompts for new questions. I’m glad we made it this far. The kiddo is glad, as promised, that it’s a short walk home.