I’d love to read Amanda Ekery’s book, but $50 really is quite a lot, as I embarrass myself by saying out loud. On Saturday, in all the space that Uptown Body and Fender has donated to create a startingly large series of Palestinian resistance murals—first, across the street, which dates back to 2014, and now in a normally closed-off alley space, dubbed Sumud: Resistance Until Liberation—people kept giving me things. A flavored ice (when my friend bought a horchata and I didn’t), an “ICE out of The Home Depot” print, a copy of The New York [War] Crimes, and a booklet explaining the provenance of all the murals in the space, and of course the music and the space are free, too. I am given a third taco when I asked for two, but I pay for it gladly, and pile lots of fried onions on it.

The music is lovely, gentle and intricate, and easy to get lost in.

But there are also a lot of stories to orient you: while I leaf through the booklet about the murals—in the shaded half of the once-parking lot that’s been converted to an installation—Ekery talks about her family’s Syrian-Mexican El Paso provenance and about anything and everything she found to give that fact context. “You know how al pastor is from the middle east, it’s Shawarma” someone says, and I’m reminded of the time Shawarmaji did a pop-up collaboration with Tacos El Precioso. But if Akery made that very on-the-nose analogy, she did it before I arrived: while I’m there she talks about evil eye pendants, cowboy boots, and says things like “I grew up listening to mariachi bands and dancing the dabke at family weddings.” She explains the Ottoman patterns she used in the book's binding.

After a very spaced out version of La Cucharacha, Ekery tells us about its meaning and use in the Mexican revolution, when no one in the audience guesses what it was (or was too lulled by sun and tacos and music). She was always interested in her genealogy, she says, but that got jump-started by seeing everything one is talking about when one gestures at "the news."

A friend with connections to Columbia—who came after I told her about it, and sent her this image of the “student intifada” with a Hind’s Hall tent—arrives right around when the music ends, and we get tacos. The guy selling stickers, jewelry, and purses tells me he’s had a good day, but he’s exhausted; he’s had four plates of tacos.

As we’re all milling around, I chat with Ekery, who is just the friendliest person; she started working on this in 2018, she says—“five years ago” she says, and we laugh—and she spent a year designing and producing the fifty-dollar art book that’s weighing on my mind, and in her suitcase she doesn’t want to take back to New York. They’ve been here all week already, doing songwriting workshops and library appearances, and next week she’ll be in Palo Alto (“condolences”) for a jazz camp with a kids (“oh never mind, kids are great”). She tells me that her band is the first event like this that they've had in the mural space, which opened in October, and it really is kind of a tremendous space to be in, with your body, while listening to music, with your ears.

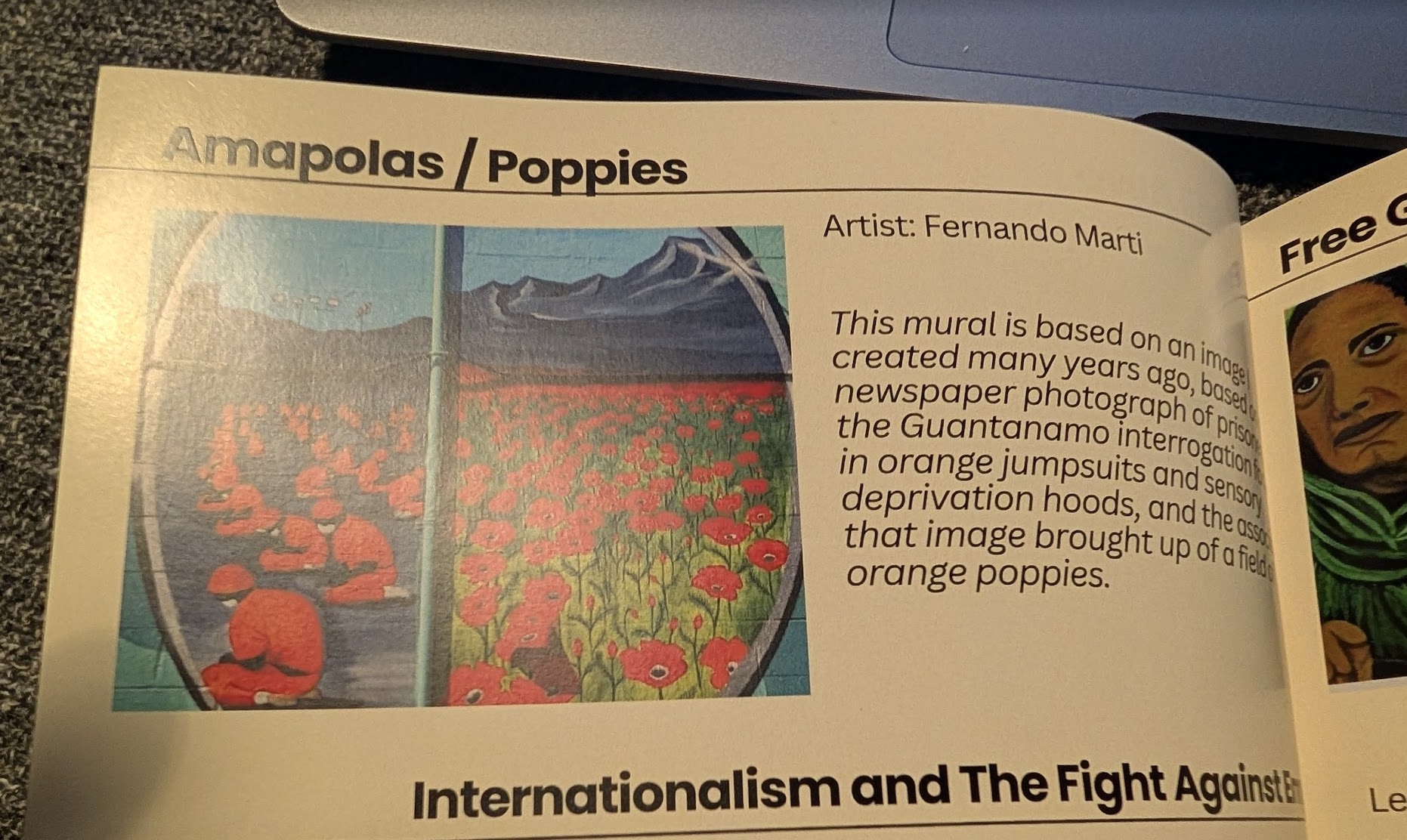

In the shady half of the space, I’m standing under this one, and I can’t keep my eyes off of it:

The Algerian MC gets on the mic and talks about overlapping struggles, about growing up hearing about Palestine, and about all the ways different peoples see themselves in each other. As I find myself thinking about how a space defined by walls has put us all together, the dabke begins, snapping the sleepy and relaxed, milling-around chair-slumpers and wall-leaners into something tightly coiled and ecstatic, all smiles and joy (and how is that lady dancing with her two kids and holding a baby?), and the people in the "end settler colonialism" shirts are dancing quick, precise, and practiced steps while others are just holding on and letting the line tell them how to move, but man, there is really nothing like dancing to tell a crowd who it is.