As I approached the corner outside Tamarack I spotted Nick Anderman, the emcee for tonight’s event, On the Waterfront: Art at Work. He was on the phone, apparently concerned. Nick and his co-organizers were still waiting for someone important to arrive, and I slipped in feeling a little relieved not to have missed anything. On the ground floor, recent issues of the labor magazine Long-Haul were available for sale, including the issue featuring the essay behind the event, “Coffee and Hernias, Cotton and Death: The Bay Area Waterfront Writers and Artists, 1977–1994,” written by Erfan Moradi and Nick.

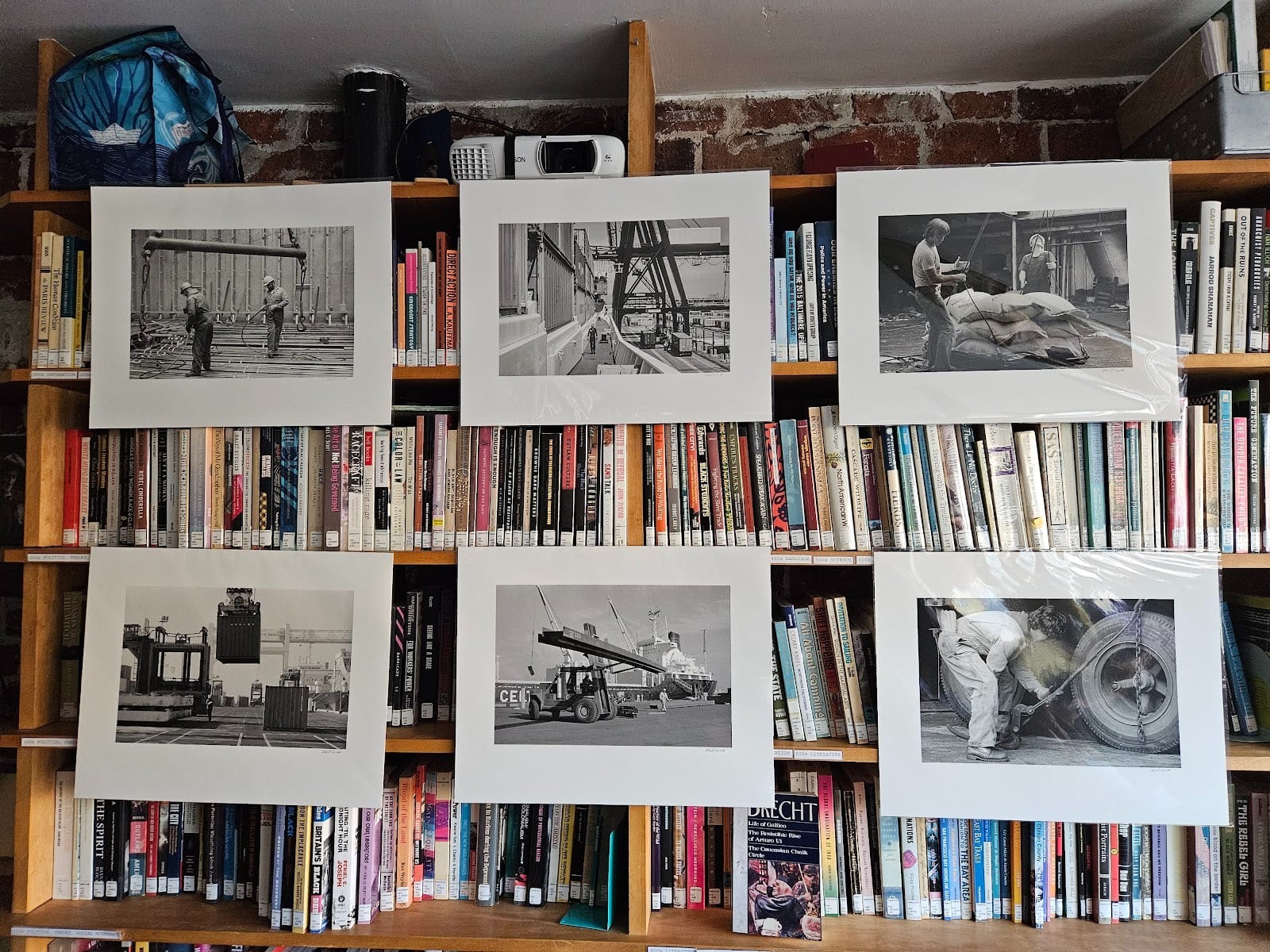

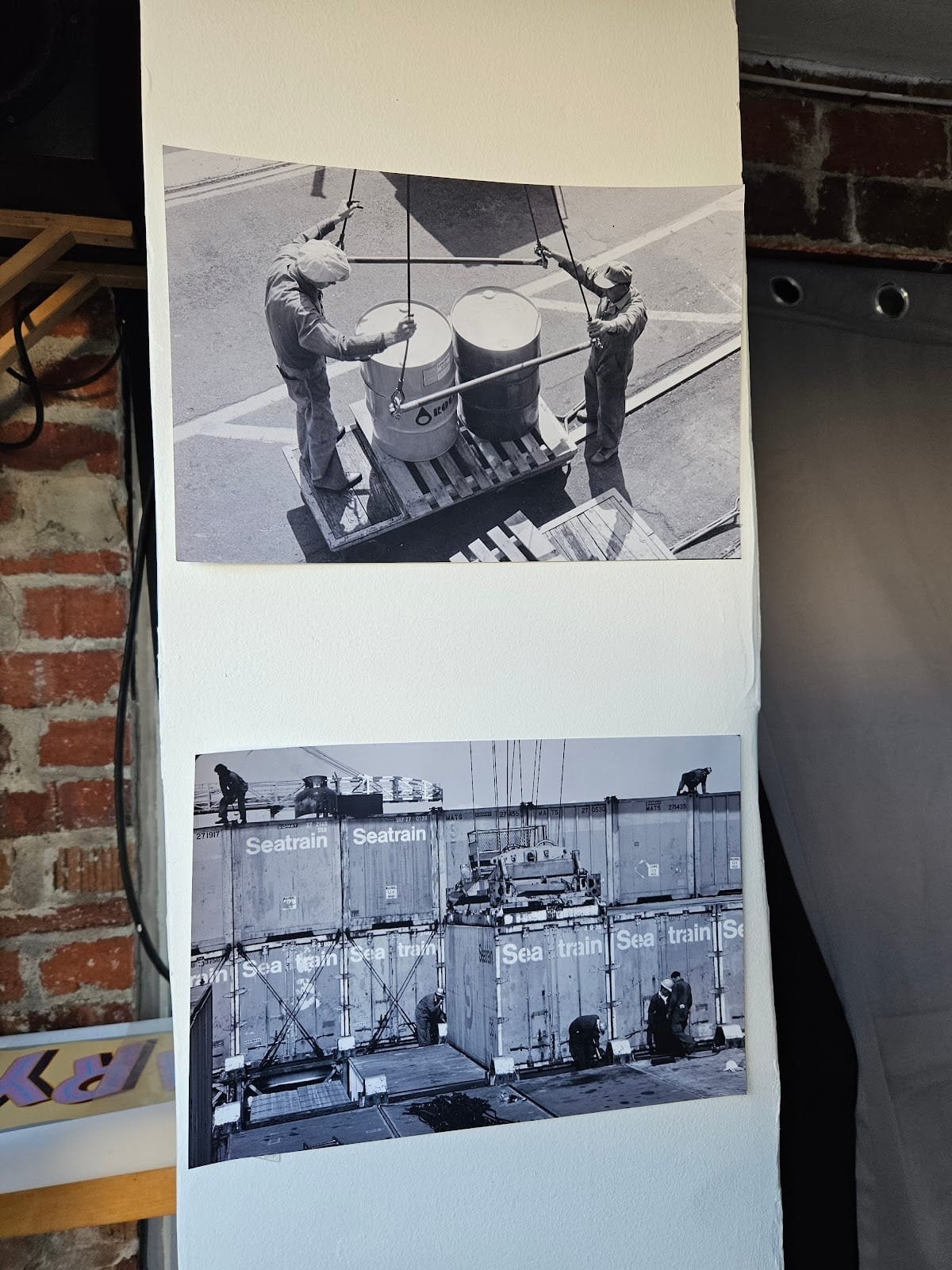

The house was packed, with blackout curtains taped over the windows giving the small upstairs space a more intimate feel than usual. Black-and-white photographic prints by Frank Silva and Brian Nelson (who were seated among the attendees) of Bay Area ports, shipping containers, and waterfront workers were hung up over the library books. A sepia group photo of the Waterfront Writers and Artists was projected onto the screen up front.

Soon after, as Robert Carson kicked us off with some of his poetry, he warned us not to follow Google Maps to get from the 12th Street BART station to Tamarack. He said this by way of apology for the delay, but it also pointed out the inability of our tech devices to eradicate problems in our lives, like “getting lost on your way to an event where you're one of the guests of honor,” and to the need to be less reliant on them. It made sense as a segue into an afternoon showcasing an archive of writing, film, and photography by waterfront workers making sense of their lives as their workplaces were transformed irreversibly by automatization. He talked about hanging out with the Beats, about Ferlinghetti introducing him to Solzhenitsyn at City Lights, but what he said that stuck with me more than the mystique of countercultural icons was how normal and commonplace it was back then to get together and make art with your coworkers.

Thanks to Nick and Erfan, much of what we watched and saw can be accessed online. Eventually this archive will also be housed in the Bancroft Library. The film Longshoremen at Work included a slideshow of photographs taken from 1969 to 1994, originally projected during readings hosted by the Waterfront Writers and Artists. The photographs dissolved in and out to the sounds of people chatting over walkie talkies and shouting to each other, scenes crowded with machines and people giving way to images of geometrical compositions of shipping containers and ports, workers unseen. Then—Bach, and a return. Close-ups on hands and gestures, workers silhouetted, standing on and among burlap sacks, the brown and red hues a stark contrast from the blues and greys of modern shipping.

I'm very susceptible to the romance of labor history and culture. I felt it when J and I opened a curtain to let in some light as Erfan read the poem “Pier 80C.” He leaned against the glass. He was literally glowing. There was something auratic in the moments when George Benet's face went blurry in the film of him reading poetry in a dance hall. Or when Brian talks about his dad being in the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, and how people would work on the waterfront together for decades. Yes, automation won, but we were all here to listen to three worker-artists whose experiences and art still help us make sense of our world decades later. Towards the end of another film, a voiceover says, “I sold my body to save my mind.”

Someone asks about that line during Q&A, saying it really stuck with her. Robert responds, thoughtfully, that he mostly worked as a clerk rather than performing physically demanding tasks such as loading and unloading cargo, and he was grateful for that. During the two years he worked as a manual laborer he broke his wrist and dealt with a host of injuries. The three men had another partner—they never really used the word “coworker,” which makes me wonder when we started to use it—who lived in the neighborhood but wasn't there, who is now paralyzed. A lot of people died, he said. You really were selling your body.

On the other hand, he said, the docks were a place where you didn't have to make yourself into someone you weren't. It wasn't that people were always nice to each other, but you could be yourself at work. There were Black men, and there were gay men who were out, some who weren't. Of course, there were only men back then, though Robert says the union fought to allow women into the industry. (Nick interjects to say that there's more gender parity in certain locals now). In response to another question about women, Robert says that they would invite the wives of some longshoremen to read at events and collaborated with cultural groups organized by tradeswomen.

For me, the picture they painted still felt something like a masculinist golden age, which I have mixed feelings about. I'm suspicious of my instinct to valorize a past and a milieu that might have been represented quite differently by the wives of the workers, the tradeswomen artists, or the Black longshoreman, but I am also tired of the use of identity politics to dismiss an era when labor was stronger than it is now. I'm tired of neoliberal identity politics in general, but still I find myself thinking things like “this group is entirely old white men,” feeding the not-nonexistent sense of doubt that things were as great as they seemed.

Yet, that morning an ICE officer shot and killed ICU nurse Alex Pretti in Minneapolis, and the state defamation campaign was already under way. It was the day after the general strike in Minnesota protesting the murder of Renée Good and so-called Operation Metro Surge. My social media feed is filled with reports about people being disappeared, people feeling afraid to go to work or to the gym or anywhere in public. During the Q&A, panelists and attendees alike shared their memories of how political the ILWU was in the 1970s, 80s, and early 90s. Half the membership was African American. They organized to stop ships with cargo on the way to South Africa during Apartheid around a decade before it formally ended. One of the audience members, another ILWU member, shared a story about an FBI officer visiting the union hall to arrest a worker suspected of theft. The worker’s comrades immediately surrounded the agent to stop the arrest. Someone threw a punch and the agent fled. The FBI never showed up again. I'd like to believe this is how hope is kept alive.–Yvonne