I’d been asking myself whether the Flecktones’ first set was a good argument against a nearly forty-year old band not choosing to reprise, almost exclusively, the first three years of their recorded existence. “The Flecktones play the greatest hits of 1989 through 1992,” after all, would be a funny way to advertise a tour. But if nothing that this effortlessly virtuosic band played wasn’t something you’re going to hear nowhere else—with as many excessively nested and interlocking musical flourishes as that clause had negatives it didn’t need—I think I do mean the word “effortlessly” as, also, “without all that much effort.”

Mind you, you will not find a bigger Béla Fleck superfan. When I saw the BEATrio in the West Bay last year, Béla was absolutely propelled by Antonio Sánchez’s endless drums, not to mention energized by the math problem of navigating that polyrhythmic space alongside Edmar Castañeda’s arpa llanero (a Columbian instrument with a secret extra bass guitar hidden inside a harp). Fuck, they were good. I listened to that album in the car coming to and from the Flecktones show—parking across from the Giant burger, on Grant, a short walk from the UC Theatre, but just outside the “don’t try to park here” threshold, which now extends outward from the university, like Sauron’s dominion, at least to Milvia—and both I and my companion had the same reaction coming and going: Fuck, they are good. Although I had seen the BEATtrio only once, at the Presidio, that night on the drive back to Oakland, I had wondered: should I throw caution and childcare responsibilities to the wind, and immediately purchase tickets for the next day’s two shows? Would I kick myself if I didn’t? (I didn’t, but: yes and yes.)

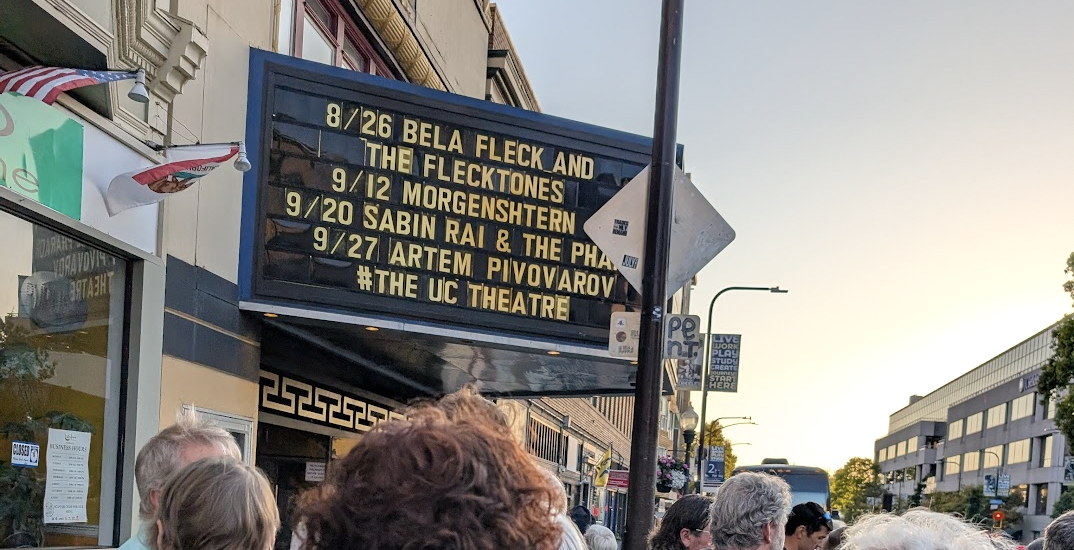

The UC Theatre was doors at 7, show at 8; the band wouldn’t start playing until closer to 8:30, and though we arrived promptly at 7—I would have arrived earlier, but had not properly conveyed the urgency to my co-concertist—the line to get in stretched along University, ok, not quite all the way to Shattuck, but almost. All those other people in line were a lot older than they had been when we all first heard of the Flecktones in the nineties, unlike me. The number of Black people in that line was small enough that my (Black) companion suggested she might hail the single exception with a jocular greeting that my own woke whiteness precludes me from relating.

It did, however, recall to mind the Columbus, Ohio, bluegrass record store—from long enough ago that calling a place a “record store” was not an affectation—whose proprietor told me that if Béla Fleck was playing in the parking lot, she wouldn’t go out to see him, not since he started playing with those “rap” guys. (“Oh!” I said to that, being fifteen years old.) Most of the tunes they would play (in what Howard Levy a little cringily hailed as “Berzerkely”) had been first recorded back when your Dave Matthews Band or your Flecktones were still describable as a “an interracial band,” back when a “Bluegrass Record Store” proprietor would cast the Newgrass Revival’s banjo player into the outer darkness for the sin of playing banjo with Black people. In the year the Flecktones were born—on a PBS TV special, if you can imagine such a thing existing—that was not, of course, a “thing” for the jazz world that Fleck was leaving behind the omni-white bluegrass milieu for. But that was a while ago, back when both he and I had ever-so-slight hillbilly accents; I once tweeted about his affected drawl, and Twitter being what it once was, he actually tweeted back something like “yeah, I hung out with a lot of kentucky guys back then.” Twitter being what it is now (nazi garbage), the search function can’t find those tweets, but I’ve also lost the accent I had when I first heard Fleck play a solo on a Dave Matthews Band song about settler colonialism and said to myself “I need to purchase everything this man has ever recorded,” and subsequently did.

By the time the show started, over three decades later, the vibe was as warm and relaxed as the family reunion it still kind of is, since Howard Levy left the band in 1993 and only came back around the time the Flecktones stopped touring nearly so much. During the pandemic, they had even announced some kind of dire-sounding falling out in the band, around a non-specified disagreement about vaccines—another scrap of text I can’t seem to coax out of Twitter, now, but which bummed me out at the time—and I had assumed the band was done, especially since Béla was clearly entering one of the most productive and ambitious phases of his non-Flecktones career. Since he turned 60, he’s released a pair of duo albums with late greats Toumani Diabaté and Chick Corea, the BEATrio album, an absolutely breathtaking collaboration with Zakir Hussain (RIP), Edgar Meyer, and Rakesh Chaurasia, and My Bluegrass Heart, which may legitimately be the best thing (imho) he’s ever done. His foray into Gershwin a couple years ago is a comparative footnote, despite the racial struggle session it sent him on; re-arranging Gershwin for the banjo has got to count as a big swing, and it doesn’t even make my top five of his big swings in the last decade.

But it has been a while since the Flecktones took any. With no new album, this is apparently just a “you know, the Flecktones? That!” tour. Other than what Fleck described as the last-minute addition of the more recently composed “Juno” (only 12 years ago), the entire first set was from the first three albums, and not even the songs one tends to remember (“Sinister Minister,” “Sunset Road,” and “Flight of the Cosmic Hippo” were all saved for the second set). Since of “Flying Saucer Dudes,” “Nemo’s Dream,” “Mars Needs Women,” “Sex in a Pan,” and “Frontiers,” only one of which is even on their 1999 Greatest Hits of the Twentieth Century compilation album, it was a little like going to see the Beatles and then they only play songs from Magical Mystery Tour and Yellow Submarine, and not even “All You Need is Love” or the title tracks.

So that’s why, at the intermission, standing among the slightly younger crowd in the standing-room-only section of the UC Theater (median age still north of forty), and exhausted after a long day of working what feels like three jobs, I had the absolutely heretical thought: what if I just went home now?

The very fact that it even occurred to me! Even as a possibility! I have seen Béla and the Flecktones many, many times—I once traveled to Slovenia to see them—and I am the sort of superfan who would compare seeing them to seeing the Beatles, without a trace of irony. But in that moment, going home was a compelling temptation. I had enjoyed myself for an hour and a half. That was fun, I thought; maybe now, bed? I saw no indication that anyone else wasn’t having a great time, but I’m sure I wasn’t the only person who wondered if bed was a more compelling proposition than more. Bed gets pretty great, at 10 pm of a Tuesday night, three decades since you were a teenager, when the Flecktones were a kind of jamband-adjacent virtuosic jazz group, whose sense of humor, face-melting licks, and hummable tunes found them an audience among the kind of people who listened to Phish and the Dead and Dave and so on. Most of the other bands they played alongside at HORDE festival type shows are less well remembered, just like the tunes they played in that first set.

My personal Béla Fleck top ten list includes only two Flecktones albums. One is Live Art, a compilation of live performances from the tours in the years following Levy’s departure from the band (more or less just because he was tired and he wanted to go home). After they did a nice album of just the three remaining members, they went on a long tour with a rotating cast of incredible guest stars; Live Art compiles some of the best and most interesting performances from that era, and it blew my ever-loving mind. Every track is a unique and marvelous moment in time, the kind of performance produced by a band that not only puts itself way out of its comfort zone but is astonishingly able to rise to the occasion, say, of jamming with a Chick Corea or Branford Marsalis, or making Sam Bush’s mandolin figure out how to fill the space left behind by Levy’s absent harmonica. That, for me, is the best of Béla Fleck: the way the coolest cat—on an instrument that turns a blurry magic-eye painting of impossible flurries of notes into crisp, hummable shapes—has spent his career putting himself in improbable combos and then fighting his way through it. (Little Worlds is the other Flecktones album on my top ten, a triple album of fiendishly complicated tunes and an absolute army of strange and interesting collaborators.)

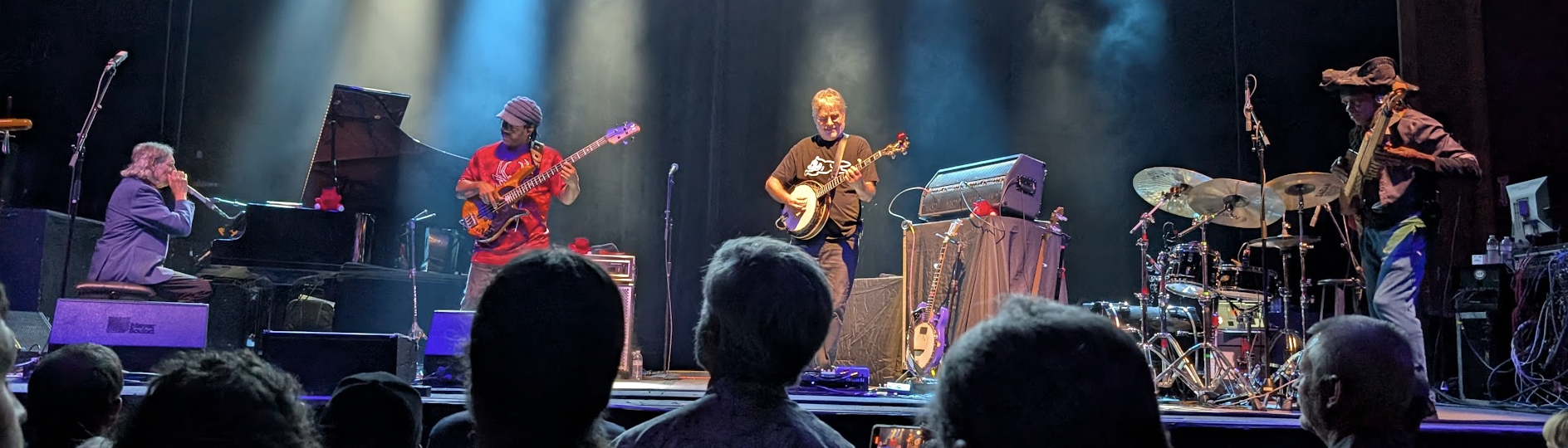

This iteration of the Flecktones feels back in his happy place, if not his juvenilia. But after I didn’t leave (because of course I didn’t leave), Béla came out from the intermission with a black headband on, at which point, the band started fucking cooking. My phone had died, which was fine, because it wouldn't be needed: After “Big Country,” the only tune not from one of the two Levy eras, they played the hits (“Sunset,” “Sinister,” the hippo thing) and those tunes do still hit. Maybe you simply have to save some of your juice for the second half, at their age? I couldn’t help but notice that Levy’s jaw-dropping virtuosity was accompanied with moments when it seemed like maybe he didn’t have quite as much air as he did forty years ago (though who does?). But if you saw only the second set, you’d want to know how these guys are so shockingly undiminished, how a band founded before the Berlin Wall came down is still basically doing shit no one else does or could. How is Future Man—who looks like a pirate these days—STILL from the future? He’s still the only person in the world who plays the instrument he invented (just like Victor Wooten is with the “bass guitar”).

Anyway, it was an incredible set, even if it doesn’t surprise me to learn that they performed essentially the same set at the Montreal Jazz Fest in 2018, or that “Juno,” the song Béla said they had worked up special, a note of last-minute spontaneity (“we hadn’t planned on playing tonight”), had also been played the night before, in Los Angeles. “Live in Eleven” is from fourteen years ago, and counts as new, too. On this tour, there are no surprises. But, inshallah, may any of us still be capable of such unsurprisingly surprising excellence four decades later than we blew people’s minds the first time. I felt no temptation to hop in the car the next day and follow them to Oregon. But I might listen to that show on YouTube later today.