When the huge Tech Week schedule dropped, my criteria for deciding what events to go to was: can I get there from Oakland after work (I was not going to take any PTO from my day job for this), is it completely public, and does it include enough of a “thing” for me to try and cover? If I were a real journalist, maybe I would request press passes for the official a16z dinners and JPMorgan-sponsored events. I’m not. I am just a collector of vibes.

For Tuesday, I went with “Better Tech for Creative Humans.” Seeing “humans” as a descriptor for people is triggering, but I am here in service of capturing what is, not what I want things to be.

The event took place at an office in SoMa. When I saw a woman with a sweater wrapped around her shoulders, well-fitting pants, and a big leather tote walk through the entrance, I realized that this would be a very different experience than the slop-filled and sloppy Monday night screening. I walked up the stairs to a check-in table, put my name on a nametag, and noticed a bag of candy with a sticker that said “STOPSLOP” on it. Ok, I thought, maybe this event won’t be as depressing as last night’s.

The white-walled office was airy and underfurnished. A panel was already underway in the room farthest from the entrance, and it had reached standing-room-only capacity. I took a drink from the bar and my hearing adjusted to the speakers as I made my way over. This crowd was a group of people who cared how they looked. Not to say everyone was stylish, but I saw enough examples of contemporary aesthetics to feel the echoes, at least, of a world bigger than tech. A room of designers, basically.

And then I tuned into the panel speakers and dropped back into reality. This would be, again, an event about AI.

The panelists all owned or worked at “creativity as a service” agencies or studios, plus an “AI visionary” named Branko Lukic. I tried taking the panels at face value at first. I tried to engage with what was happening. Truly! In practice, this meant furiously writing down why I disagreed with everything the panelists were saying. I heard sentences like, “There used to be a creative class, but now everyone is a creative” and “All you need to do is visualize and write out what you’re visualizing,” and even “It’s not just Coke that can make a Coke commercial now.” Though each panelist gave their own requisite caveat, how there is “no accounting for taste”—and how, therefore, the human element of producing any creative work will never cease to exist—those caveats felt half-hearted, on borrowed time. I got the sense these panelists needed to telegraph just enough care for their target market to willingly close deals.

Otherwise, it was all boilerplate AI conversation for the creativity-only-exists-with-an-end-consumer-in-mind set. There was one concept that struck me as underexplored in the broader “what does AI portend” discourse, though. We mostly read and hear alarms about AI deskilling or its quality-flattening effects or the potential replacement of entire existing workforces. By contrast, these panelists were fantasizing about how AI allows for the logical extension of the neoliberal worker, the worker as human capital, that is, as an agglomeration of value-accruing inputs and nonexistent protections. “One person can be an entire production company now,” one of the panelists said. “Take your ideas, use the tools to make every version of it happen, and enter the creative marketplace.” In that sense, perhaps, the tools are not threats to the creative’s labor; they are taunts, demands, now-nothing-stands-between-you-and-complete-self-exploitation magic wands.

After two panels of this, I gave up. The two audience questions I stayed for were smart and skeptical, but unfortunately for them, the panelists were in the business of marketing, and there would be no real engagement with the cracks in their arguments. I checked the Tech Week schedule on my phone and decided to give something else a shot, as long as it started at 7 PM and was within walking distance, preferably in the direction of getting back home to Oakland.

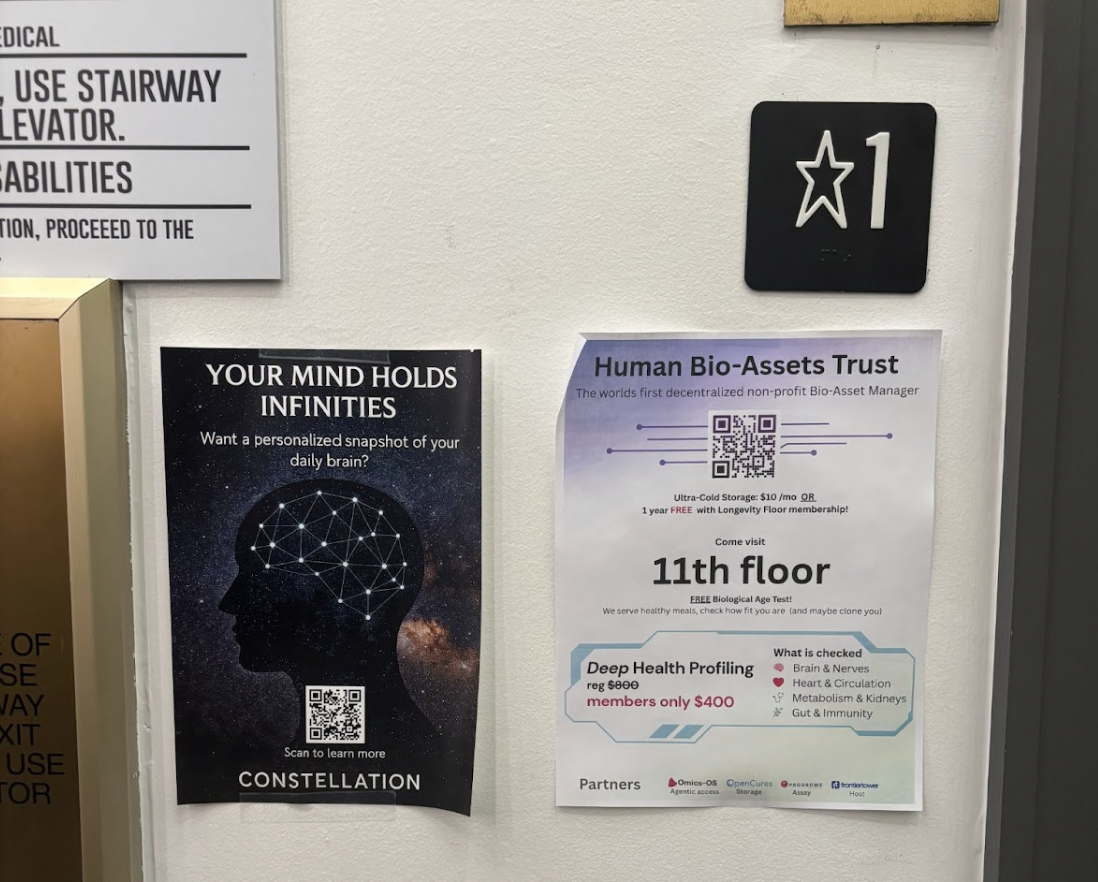

As it happens, I ended up at the densest confluence of contemporary tech signifiers I could’ve hoped to find at Tech Week. It was the Frontier Tower, a “vertical village for frontier technologies” (it’s a co-working space). Though it was immortalized in Kerry Howley’s recent New York Magazine piece, I didn’t make the connection at first. But I started getting keyed up when I saw the longevity flyer near the elevator and had to press one of the buttons on the elevator that advertised things like “Biotech Neurotech” on floor 8 and “Accelerate!” on floor 10.

I was heading to floor 6, “Art & Music,” for an “Art Pop-Up at the Frontier.”

The empty warehouse space reminded me of art shows I’d been to in LA in the mid-2010s that ended up being extensions of the skater-and-stoner universe: Dim, ramshackle, and displaying art that hangs heavy under the weight of its own straightforwardness. I saw photos on display of Waymos driving down streets with AI billboards in the background, psychedelic art, and a sculptural representation of a vagina. As the electronic beats thrummed in my ears, I found I didn’t have the energy to talk to anyone. I saw two clean-cut teenage boys and wondered to myself why they were here, and did not try to find out.

But then, strewn on a couch against a wall, I saw the only thing all night that felt inspired. It was piles of what appeared to be homemade magazines that advertise various places in San Francisco. Each place included a dreamy, anime-style photoshoot featuring the same cosplay-esque individual, an androgynous figure with a spiky wig, incredible bone structure, and a clear love of being photographed. This individual at Land’s End, at Dumpling Time, at Craftsman and Wolves. There was even a magazine with actually good steampunk-anime-noir photos from inside city parking lots. Most of the text was in Japanese.

By all measures, these objects should be bad—it’s pretty random to do your own photoshoot advertising State Bird Provisions on Fillmore. But the commitment to a vision, the obvious labor of producing them, and the uncanny is-this-a-game-or-is-it-art quality left me captivated, and I felt giddy flipping through them. Their covers described them as free photo books and San Francisco travel guides, but I was too nervous to actually take any of them. Instead, I took photos of page after page, feeling like a spy in a Cold War thriller trying to obtain secret documents by photograph. I got to experience the visceral and life-affirming sensation of encountering something I couldn’t put my finger on but that felt like the world expanding in front of me.

When I showed photos of these photos to my girlfriend once I got home, she asked how sure I was that it wasn’t AI. I couldn’t answer. What if a gut feeling is not a strong enough heuristic? If they actually are AI, well, fuck me.