Until recently, Huchiun Park was too new for street view to show you anything but the recently emptied space it was built on. Its young trees are still too small to give much shade, though you can use the adjacent, recently constructed buildings to block the sun, if you time it right. Mostly you can’t. Mostly it’s all a very bright space, very exposed to the sky. But it’s the playground and park my three-year-olds always want to go to, these days. They used to call it “Train park,” for the trains that periodically pass, and although they ask for it by name, now, they got the wrong name fixed in their heads, at some point, and I’ve been unable to correct them.

It doesn't matter. When they ask for “Hochial” park, I know what they mean, so we go.

It's a space filled with what used to be here. In 1859, for example, as the Emeryville Historical Society explains, an Anglo settler named Edward Wiard built a racetrack here, after he “purchased a 115-acre tract of land along the shoreline in an area that was once occupied by the native Muwekma Ohlone people and more recently owned by Vicente Peralta as part of Rancho San Antonio.” That kind of here is what used to be here is everywhere. If you walk around the area even a little, you’ll see EHS’s signs and QR-code enhanced walking tours; one that follows Park Avenue back to where you probably parked, on the way in and the other follows the greenway north up to Bay Street mall.

These signs will tell you, for instance, about the vice that clustered around Wiard’s racetrack: the gambling, saloons, brothels, and hotels that would give “Rotten City” its nickname. That vice would also give Emeryville its borders, when Berkeley and Oakland were both expanding, and when religious and anti-gambling reformists were also on the rise, so local “business” leaders drew the new city’s boundaries to protect their interests, keeping the vice around the track in but keeping the the Golden Gate District’s churches out.

Containers can outlast the thing they were built to contain, however. The racetrack only survived another fifteen years, after which everything was cleaned up and industrialized. Pixar is now four blocks away, built on top of what had been a five-acre canning plant; what’s now IKEA was once Judson Iron Works, and so on. Mostly what used to be warehouses or factories is now housing.

The land the park is on hosted the Sherwin-Williams paint factory for about a century–complete with iconic freeway sign–until they decamped, as the Athletics would, for Nevada. After Emeryville dug up “57,000 cubic yards of lead, arsenic, and VOC contaminated soil” onto conveniently-adjacent trains, apartment buildings clustered around the recently cleansed green-space and playground, the way vice was once drawn to the racetrack. And in 2023, after some extremely local controversy, the city settled on “Huchien” as the name for the park, a transliteration of Xučyun: having rejected the extremely Anglo-era names offered by the Emeryville Historical Society, the land would be acknowledged as the ancestral and unceded land of the Chochenyo speaking Ohlone people, as well as an English word for “this playground” that my children happily garble. The Confederated Villages of Lisjan holds protests at the Baystreet mall, nearby, when the American word for now is “Black Friday.”

The park was inaugurated at the city’s 2023 Harvest Festival and hosted this explosion of political violence at 2024’s Harvest Festival, but the scene was calm on the 2025 edition, a few saturdays ago. There were pumpkins to be decorated–free of charge, which confused us–games were laid out on the green space, and a variety of informational stalls and food trucks clotted the walkways, with swarms of orange-vested volunteers helping out everywhere. A two-spirit drum performance was cleansing the area of any lingering bad vibes, and I gathered we had just missed the mayor. I was only very briefly able to chat with the EHS folks, but they told me they had a third walking tour in the works, one that would go up San Pablo, for the “more adventurous.”

As we left, a muralist was getting ready to fill this empty space in the adjoining community garden with what he told me would be “sort of like that flower arrangement,” pointing to a nearby space divider covered with flowers:

All of it was gone the next day. Most days when we come here to play, the only things scheduled are the trains that pass by, two or three times a play session. Most of the time the time is as empty as the space.

The playground itself: It’s a good one, inviting and spacious. The swings, the slide (the rattly roll-y kind), and the climbing tunnel are all surrounded by rubber ground that slopes in ways that make it fun to run up and down, with low walls a toddler can climb and walk along (but not hurt themselves if they fall). The wooden modern-art-ish looking climbing poles and mirror maze on the other side of the lawn stop being “play structures” when there aren’t kids in them, but they play the role well when there are, and that's the story in general: it’s a space filled with space, far more empty picnic tables than people, and a broad lawn that fills up with dogs and their people around dusk, but mostly just empties back out when they leave. It’s a still space, mostly filled with what isn’t here, which is mostly still and empty space.

Someone keeps the space clean, clearing away anything anyone leaves there. And just like I just cleaned my own kids out of all the pictures above–using the weird AI tool that appeared on my phone one day, without my particular consent or desire, and I thought it was a little creepy, and then one day (today) I found myself using it, on purpose, and was surprised to find myself happy that it works so well–it's a nice thing, but leaves a lingering... something. A feeling about how well it works, and how you feel about the fact that there are no toys left out on all that clean and bare ground, none of the generously discarded carts and wagons and jumpers and other adopted trash that you’ll find at a playground to Huchiun's east, in Oakland, parks like Temescal Creek, Dover, or Frog.

Emeryville playgrounds all tend to be like this (Davenport and Doyle-Hollis come to mind), though I don’t know whether someone you don’t see comes to clean them at night, or if people just know, without being told, not to leave toys for other people’s kids to play with. My mind goes to the shellmounds that once testified to the thousands-year occupation of this land by thousands of years of indigenous people, that were filled with all the detritus of thousands of years of life, and how they were dug up and carted away, a century ago, and how perhaps, so it goes, too, with anything people leave here. I'm overthinking it, of course. But that's what you often find yourself doing, when your kids are playing and you don't have anything particular to do but overthink the space you're in. Maybe these days, the clean openness of the space testifies to the mode of life of the people that now occupy it.

I know, for example, that an orange couch once appeared, a surprisingly clean and pleasant couch, and I was startled enough by its presence that I thought I took a picture of it. And then the next time we came, it was gone, and now I can’t find the picture on my phone.

This is where it was, though:

It's nice. All that empty clean space is pleasing to look at, and be in, and the gardens are nicely and neutrally maintained, and perfectly complement the grey flooring you know you’d find inside the apartments. You wouldn't be wrong to call it all a gentrification aesthetic, but you also wouldn't be wrong to note how non-white the families here tend not to be; this very YIMBY city has managed to double its population in the last twenty-five years, less by displacing prior inhabitants (of which there weren’t many) than by building rental housing where blighted industrial ruins had been, or abandoned factories and warehouses. Here–as there so often isn't, in Oakland–there was money to clean it all up and build a place for people to live in, and to play.

When my kids were a little younger, it was stressful to bring them here. The play area was fine, but younger toddlers would lose interest in the official play structures, and would start walking along the walls and ranging outward, climbing around the tables and chairs, and then wandering farther out, into the street, which–though calm and mostly carless–is still a street, where a child’s life could be separated from their body with frightening ease and finality. With younger kids, a fence-less park should have more gravitational pull, more stuff to keep the kids oriented inward; this park’s spacious center doesn’t hold, and offers too many pathways outward, by design.

The bike path, for instance, will lead you toward the Baystreet mall, built where the shellmounds once were. The fences along the way are secure at all the places where a toddler could get hurt or die if they weren’t, as you walk towards the newly renovated food court and play area, where you can get pizza, where you can play with giant connect four games, and bang on the resonating tubes with hammers whose strings are much too short; as you walk, you’ll find that it’s hard to get them to slow down, or turn back: all those stairs to walk up and down, on your way there, all the public exercise equipment along the way (which is fun for the kids, who are the only people I ever see playing on it). But it’s a long walk for younger toddlers, and too much sun will hit your bodies. Well before you turn back, they will get much too hot and tired, and they will melt the fuck down.

(Most of the time, no one will be there to witness it, or if they pass, on their way somewhere, they’ll just give you a sympathetic glance and move on.)

These days, however, my toddlers can hack it. We come on early morning weekends, and after navigating exactly the parts of the playground that used to be stressful (because if they fall now, it’s fine), we take the greenway to the mall area, which we’ll have to ourselves, except for friendly security guards. There are many staircases here, too, where your children can re-enact the “So Long, Farewell” song from The Sound of Music, if they are so inclined. Every time we come, they find some new aspect of the landscape to convert into a play site, because that’s what toddlers do.

As we walk back toward “Hochial” park, picking flowers from the flower beds that we probably shouldn’t pick from–but you also can’t tell that we have, so lavishly abundant are they flowered–I’ve decided that the last year has done the park good, not only in allowing my kids to grow enough to be able to enjoy it, but also that it feels a bit more lived in. The water fountains work in the way that so many older water fountains don’t and the public bathroom is clean and maintained, but I’ve started to see a few regulars here, and learned some of its rhythms, like when the people with the dogs congregate, or when the people bring their yoga mats out to salute the sun.

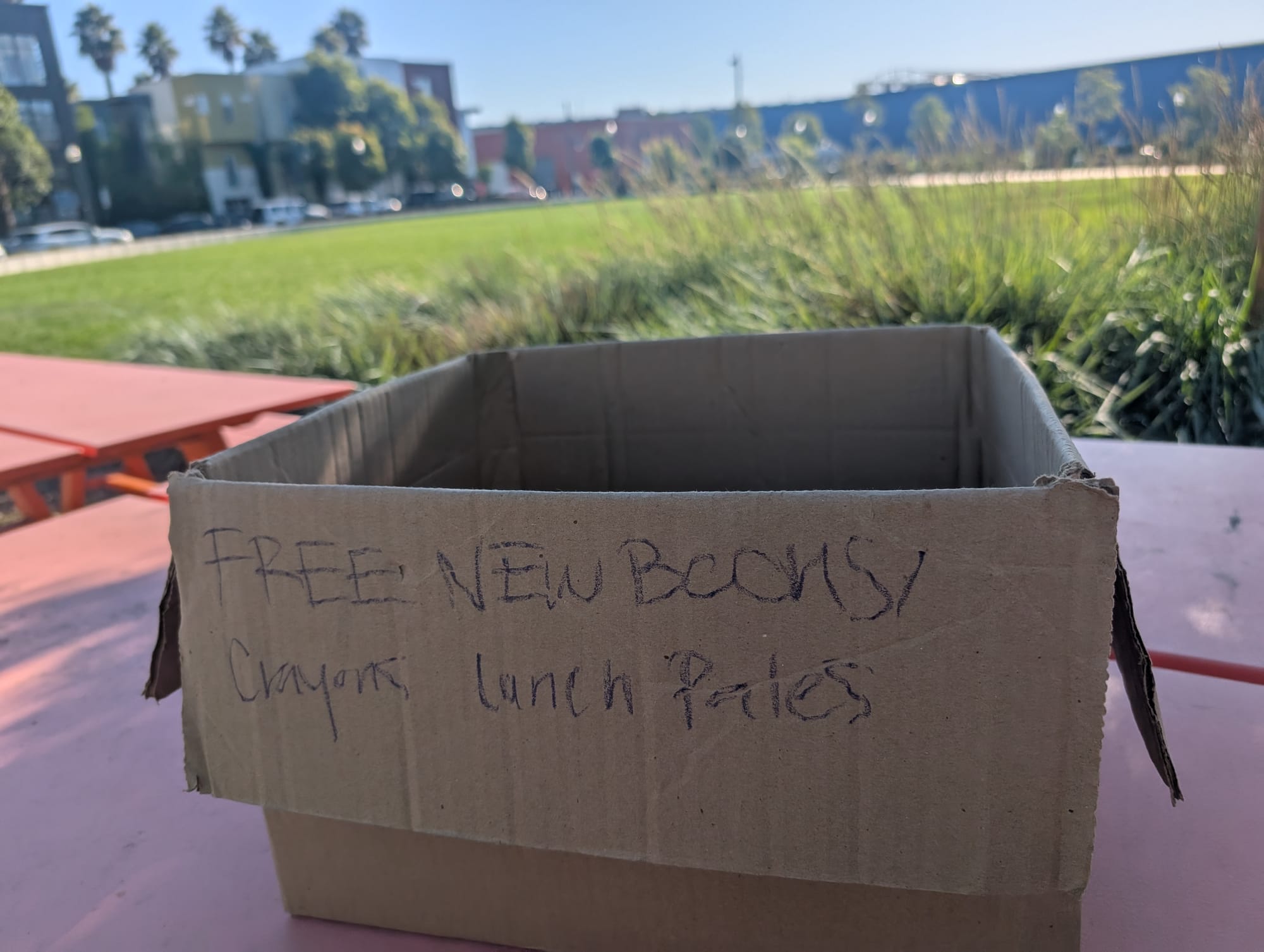

And then the other day, someone had left a box of crayons and coloring books, and we colored in the empty spaces on the page, and then they were still there the next day. No one decided to remove them, or maybe someone decided: no, this is for whoever wants it, this is not trash. It was the sort of thing the space didn't used to feel like it had. But maybe that's just how spaces grow, like little trees that need nothing more than time.