We signed up in advance, and a few hours ahead of time got the address by email: a warehouse in Fruitvale that, by the time the hired car dropped us off, had dimly merged with its neighbors under a blanket of rain. We hustled up the slick sidewalk, past men in shiny outfits hauling equipment off a truck, and into a lobby where names were checked, Covid tests verified, and passage granted.

“Re-Animation” was the loose theme: 2025 was dying and why skip out on a last party over its corpse? Black lights shone, a DJ system squelched, and on either side of the rail tracks set in the floor, several days’ work had gone into setting up art installations of the experiential sort. Ice blocks dripped under LEDs. A flickering eyeball on a television monitor dispensed printed fortunes. A trailer was tricked out like a car wash; pass through the industrial scrubbers and find yourself in a pillow-heaped lounge where psychedelic video projections can be cued up with a MIDI controller. Approaching a table that I had hoped was the bar, I ended up inside another art piece, ushered behind a hanging tarp to position my face in an aperture so that my friends could shoot boba pearls at me from straws.

(The object—to land nourishment in my mouth—was eventually accomplished, at some cost to my hair.)

The organizing collective patrolled the scene in lab coats and Beetlejuice stripes, answering questions and taking photos. Many of them used to do Burning Man, I gathered, but these days preferred smaller and more local happenings. I admired a young man’s telephoto lens, and he introduced himself as Maximilian.

“Oh,” I said tactlessly, “like the emperor the French installed in Mexico.”

“Three glorious years!” said Maximilian. “He was the greatest pointless emperor. He was the Napoleon the First of Napoleon the Thirds.”

Even if he’d been using that line for a while, it was a good one, and I laughed.

At midnight the DJ paused, a giant pulley-operated skeleton began to flail, and an unintelligible announcement echoed off the ceiling. Four or five different countdowns started in the confusion; nobody knew which was the real one. Champagne was handed out and kisses were exchanged. We went outside and watched Fruitvale’s fireworks light up the sky.

“I am a scientist,” a woman in a colorful top hat was saying, “and I told the costume scientist, it’s okay about the countdown, in science there’s always a margin of error. I don’t think he got it.”

She turned out to be an entomologist who worked with invasive species for the county agriculture department. Any research involving live animals, she told me, required formal committee approval, “unless that animal is an insect, and then you can cut right into its brain. We think insects don’t feel pain. But really it’s just that in order to tolerate what happens to them in the course of their development, they need to have sensory systems completely unlike ours.”

“Like metamorphosis?” I asked.

“And molting. Imagine that you have to take off your entire skin, down to the insides of your lungs.”

“Yuck,” I said, and then, “I thought insects didn’t have lungs?”

“Okay, yeah, I said lungs to make my point, but really it’s spiracles. And they go way, way down. Imagine molting the inside of your trachea.”

“Arachnids have book lungs,” said a passing man in another top hat.

“Fight! Fight!” shouted a bystander.

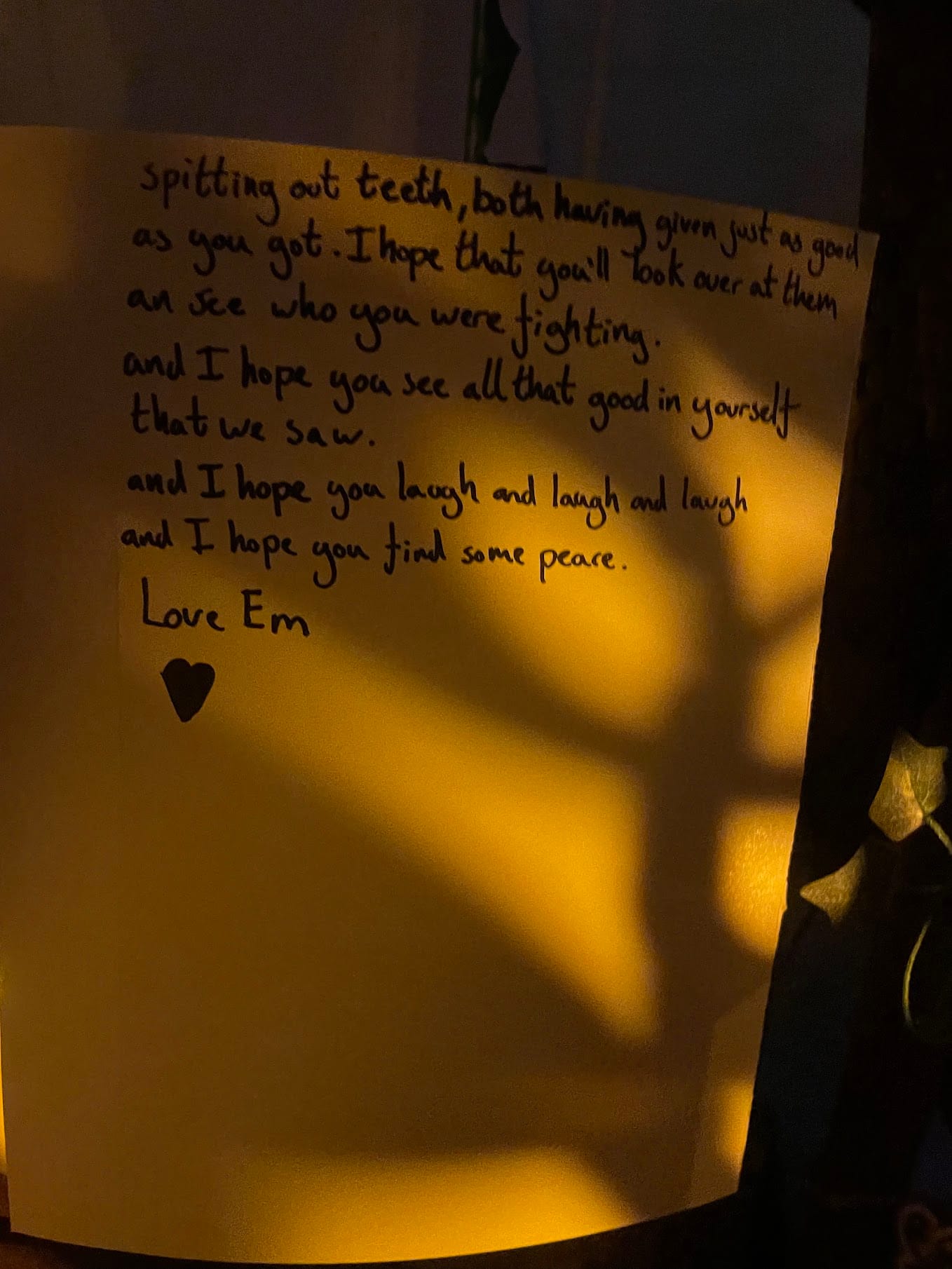

Under a makeshift rain shelter, an installation had been set up in the form of a chapel. Leaves and flowers bedecked a frame of wooden arches, under which lanterns lit two miniature piano keyboards. One set of keys controlled a synthesizer thrum; the other triggered mechanical chimes that rang out softly, in key, from surrounding alcoves. The artist, a gentle-faced hardware virtuoso named Em, had constructed the chimes from discarded nitrous oxide tanks, retrieved from the house of a close friend who’d become addicted to the gas. On Christmas Day 2025, some months after the chapel was finished, Em’s friend died. I watched partygoers file in, try out the keyboards, read the farewell note posted among the flowers and fall silent.

“It’s okay,” one said. “I can be sad for New Year’s.”

Em and I played a duet; they kept up a pulse of chords on the synthesizer and I rang simple arpeggios on the chimes. Everyone I know has had their heart broken by 2025 in some way. It’s worse than the cascading unreality of 2020 in that the surface fabric of normalcy never ruptured. We kept going to work, seeing our friends, making our children believe that the world made sense, all the while knowing the bottom was falling out. The dancers under the black lights, the goofy art pieces and the serious ones were trying to work their way out of time, to prolong the gap between one year and the next. I left the warehouse hours after midnight with a raincoat that I thought was mine and turned out to be a stranger’s. Auld lang goddamn syne.