Should Sinners have gotten more Oscars nominations (16) than did the previous uncontroversial standards for cinematic excellence, the three greatest films ever produced, All About Eve, Titanic, and La La Land, which got 14? For a hot minute, this question will have been debated in the place where the worst opinions are fought to the death, social media, before that discussion, digested, is allowed to sink back into the primordial nonsense out of which it was formed. It's social media’s job to attract (and contain) this kind of vampiric metadiscourse, and it does it well. Can you imagine if we had to have these conversations somewhere permanent?

But it's a bad question, fundamentally. It’s bad because “Who deserves the Oscar?” is a not-even-wrong question, up there with “Who deserves the Nobel Peace Prize?” Such prizes so reliably don’t go to who “deserves” them that they collapse the very concept of deserve in that context. Demanding the Academy up its game is like calling on Trump to serve the American people better: you can do it if you want, but there will always be more worthwhile things to do with the air in your mouth.

The case “against” Ryan Coogler’s film is that it’s only good, not great. But if you ever find yourself invested in the argument that the number 16 should be something lower than 14—perhaps a self-respecting number like eight, or even a decent, humble six—you should take up honest labor. (My excuse is that I’m on vacation, though that still applies). But as silly a hill as it is to die on, there’s a better question buried in it that I'd like to raise up: Is there an important and knowable distinction between a movie that is merely very good and one that is actually great?

I don’t really think there is. Or, if there is, it’s only available in and through the sociopolitical context by which we experience the work. Critics might come to a robust consensus on the difference between good and bad movies, and even how the ambitious or innovative very good movies are distinct from the ones that merely do their job well. But hardly anyone agrees to any real or lasting extent on what constitutes greatness, on what makes a movie surpass the merely “very good” and become, in some sense, immortal. I think a lot of folks would like to imagine that a work of art can rise out of its context and become a thing for all times and places; if forced to historicize it, I might suggest it reflects a post-religious desire for Art to take the place of God as vehicle for defeating death, that might have become generalized in the way Shakespeare made his mistress immortal by putting her in a sonnet (once everyone decided to agree that Shakespeare and “great” were synonyms).

But in observable practice, I would put to you that “greatness” so obviously flows out of the subjective taste of the individual critics who make the canon, at the time they do it, that no consensus on it ever could exist (except insofar as it takes on institutional weight). When “greatness” is claimed, it always has as much to do with what that moment is seen to require from the artist as what the artist produced. That’s as true for the greatness of Shakespeare as it is for when Jeanne Dielman pushed her way past Vertigo and Citizen Kane in the 2022 Sight and Sound poll, which says interesting things about what was wanted or needed from art in 2022, even if those three movies were all the same as they had been in 2012. Only their context had changed. And you could put a hundred other titles on top of that list, and I could easily talk myself into agreeing (even if my hundred wouldn’t look all that much like yours).

Still, if you want to argue that Sinners is only good, not great, then it’s possible to start by saying a true thing: That the academy’s tastes are not only responsive to the cultural and political moment, but are shaped by predictable and unsurprising ideological perspectives in how they do so. This is of course true. But the moment you suggest that they are overvaluing a Black artist’s production–because white liberals like to congratulate themselves for being woke allies without embracing truly radical art, a hard-to-deny proposition–you have begun smuggling in a much stronger and harder-to-support claim. You have started with that true thing about the measuring tool’s inadequacies and have used it to make a claim about the thing it’s “mismeasuring.” But that’s not how it works. Critiquing the academy for its particular and predictable taste—that the Academy Award is going to go to who the academy awards—cannot diminish the film in question, precisely for that reason. To the extent the number of nominations says something about the academy, it by definition says nothing about Sinners. And yet people who say a lot about why the academy nominated Sinners tend not to leave much space to make their actual case about the actual movie. They tend to sort of downplay the things people say in its favor—not arguing against them, just kind of accepting them but diminishing them a bit—while gesturing, vaguely, toward the kind of movie that should be getting those awards, independently of whether any movies necessarily exist, this year, that would have better filled that role.

Sometimes being unmoved by a highly praised movie—as I was by One Battle After Another—is a sign of a keen critical intelligence, the fact of a stalwart and brave critic being unmoved by the crowdthink of our media hivemind, and just generally seeing to the heart of reality and Art and stuff; in those cases, it’s totally fine for me to be like “okay, this is fun but doesn’t really make a ton of sense and its politics are actually kind of annoying? Like?” That’s totally fair, and the sign of a penetrating intellect. At other times, however—as when you are unmoved by a movie I liked a lot—it illustrates our society’s benighted media illiteracy, which has reached truly dispiriting depths in your particular bad take. So let me talk about Sinners, to explain your failings to you, patiently, wisely, and with frankly stunning amounts of literacy, which is a word that means “knowing what words mean” (which I do).

◎

Sinners is WAY too much movie, a level of movie one might even say filmmakers are proscribed from producing. Period drama about race AND vampire slasher? A genre movie with Ideas? In this economy? This fact is, on its own, a wholly adequate explanation for why it got so many nominations, especially in an austere cinematic context where the crumbs we are given have to be treasured like rare and precious jewels. Sinners does a bunch of different things well that you wouldn’t think would be in the same movie, and the most remarkable thing about it is that it somehow still works. Coogler messes around with aspect ratios and generally commits cinematography; Sinners also fucks and has vampires, and there's great music in it, both the kind you notice and also the kind you don’t until you listen to the soundtrack. There is subtle acting, and immaculately constructed backdrops and set design, and there are also over-the-top performances that chew the goddamn scenery (complimentary). It has jokes and there’s real pathos in it. It's got two Michael B. Jordans! Most interestingly, it's a “race movie” that declines to be segregated, and manages not to be; set it next to Jordan Peele’s work in the way the genre film is being made to do interesting and novel things with how race can be thought through moving images and sound. Set it particularly next to Nope in how it’s particularly a movie about How We Make Movies Now (derogatory). Also: It’s a movie which made gobs of money for all the rich people involved but also lets us tell a story about how a plucky Auteur fought the system and won.

It is, in short, exactly the kind of movie that gets awards: a movie with lots of different movies in it, that gives you lots of different ways to love it. Sinners is far more that kind of movie than most of the other movies we might include in our private lists for 2025. If you want to argue that One Battle After Another is the more deserving title, for example, you might convince someone who likes the kinds of movies you do, who likes that specific kind of movie; Sinners, however, will win over people who like very different kinds of movies than each other, because it simply is several different kinds of movie at once. And the largest number of Oscar nominations (and wins) will always go to movies that can win points in every category, especially if, after you watch it, you go “Now THAT was a movie!” as you walk out into the street. Nominations and awards cluster on the kind of movies that inspire instant over-the-top reactions, and which then, in the weeks and months that follow, also attract predictably revisionary takedowns based on the sense that the movie is overrated.

Okay, you might be saying, that’s all fine, but: Do you actually think Sinners is actually GREAT? And yes, I’ll respond, taking the bait and dying on that hill too, like an asshole who thought Nope was Jordan Peele’s best movie (and is enough of a critical parasite to be drawn into your trap). Sinners actually is great. But it’s great, in a nutshell, because it’s about the dangerous appeal of greatness and immortality, and about the struggle not to invite it in. It's a movie that says something interesting and important in 2025 because decides, in the end, to be a genre film, and to make art instead of Art.

Here’s what only the incredibly large numbers of people who loved this movie—maverick intellects each of them—are sufficiently media literate to ascertain: While being completely successful in terms of what it puts on the screen, Sinners is also, itself, a metadiscourse about Ryan Coogler’s journey through Hollywood. It’s a movie about making Fruitvale Station, Creed, and Black Panther—a pretty stunning unbroken string of excellence—and then waking up one day to find himself making Wakanda Forever. It’s about how, putting on your own show for your own people in their own time and place attracts vampires, who are studio capitalism, who eat you by loving you and making you immortal, at the price—perhaps—of losing yourself. It's about realizing that you invited them in.

At its core, after all, Sinners is the story of some people who try to put on a show, for their own people, at their home—a contextually appropriate experience that connects the individual to their larger communal story—but it’s the very particularity of what they've created that attracts a very specific kind of monster, who loves and appreciates that show, but who wants to kill and eat it in a very specific (and tempting) way. Coogler's twist on vampires, after all, is that they don’t just live forever; as they do, they share all their memories and knowledge and function as a kind of living hive mind in the present, a total and complete archive of all their memories, preserved forever. In that sense, they are not, in a way that's specific and tragic—and oddly very much of our Pluribus moment in which AI is absorbing and eating culture and killing the culture in doing so—individuals anymore.

What individuals do is die, and mourn others who die; the human collective does continue, and the species, but in a very blunt way, death is what makes us individuals, and vice versa. Stories continue, but in a crucial sense, only because your story can end, and will. Coogler's vampires are attracted to blood and art, the movie coherently implies, because they can’t make any of their own. They cannot die because they are not individuals (and vice versa), and this is why they cannot make anything new (again, a lot like AI). It’s not only that to be death bound—to be capable of feeling and fearing pain and loss—is what makes art possible, and gives it meaning, though that’s an important part of it (and why this is a movie so specifically about the Blues). It’s that creating art literally means and requires hitting the point where you say “this is done” (and, implicitly, admitting that the piece in question is limited, imperfect, and individual). If Jeanne Dielman is great, after all, it's great in a very different way than Vertigo is great, or Citizen Kane (or Sinners), and only succeeds because Chantal Akerman didn’t try to make it great in the way those movies are great, also.

There is no work of art without an ending, without the point at which the work ends (even if the world continues); there is no individual work of art without the relationship between it, as part, and the rest of the world, the whole. Being one thing means not being all the other things. But the problem with the vampire hive mind is that they are all the other things, too, forever and together; they are, themselves, too much all at once. This also means, then, that they are, as a cursed result, nothing in particular. An individual simply doesn’t and shouldn’t know all of everyone else's memories. Without death, without loss, and without the space between my body and yours, separating my memories from yours, we cannot make art or desire or feeling. We can only be contextually appropriate by having a limited number of contexts, by not having all the other contexts too.

This is why, for example, the vampires in Sinners are appealing and even virtuosic, but also unsettling and incredibly corny. Vampiric deindividuation is why they're always hungry, why their dances are uncannily coordinated and in unison: No one can create anything new because they're all just downloaded into the same immortal hard drive. They are no longer contextually appropriate, and can never be; they can no longer feel the right things in the right places, because without death, without individuality, they don't have a right place. The most they can be is parasites on people who still do feel, and who still die; because they cannot create, and they cannot feel, they need and are attracted to those who can. This means that the promise they make—join us and never feel pain and live forever!—is true, but misleading: they want to take and upload your feelings because they cannot make any of their own, precisely as a consequence of the gift they will give you (of having ALL the feelings, and therefore none). Again, they are a lot like an LLM in this endless hunger for new content, which they use it to create more weirdly competent emptiness. It sounds and looks good, but it also sucks, because—in its deathless hunger—it has to keep going, keep absorbing more and more of the novelty that its immortal totality can no longer generate. The kind of culture work that the vampires want, and cannot have, is about and derived from loss, death, and individuality because those are good things. Those are what the blues are all about, and also all art, of which the blues are both a metaphor and an example.

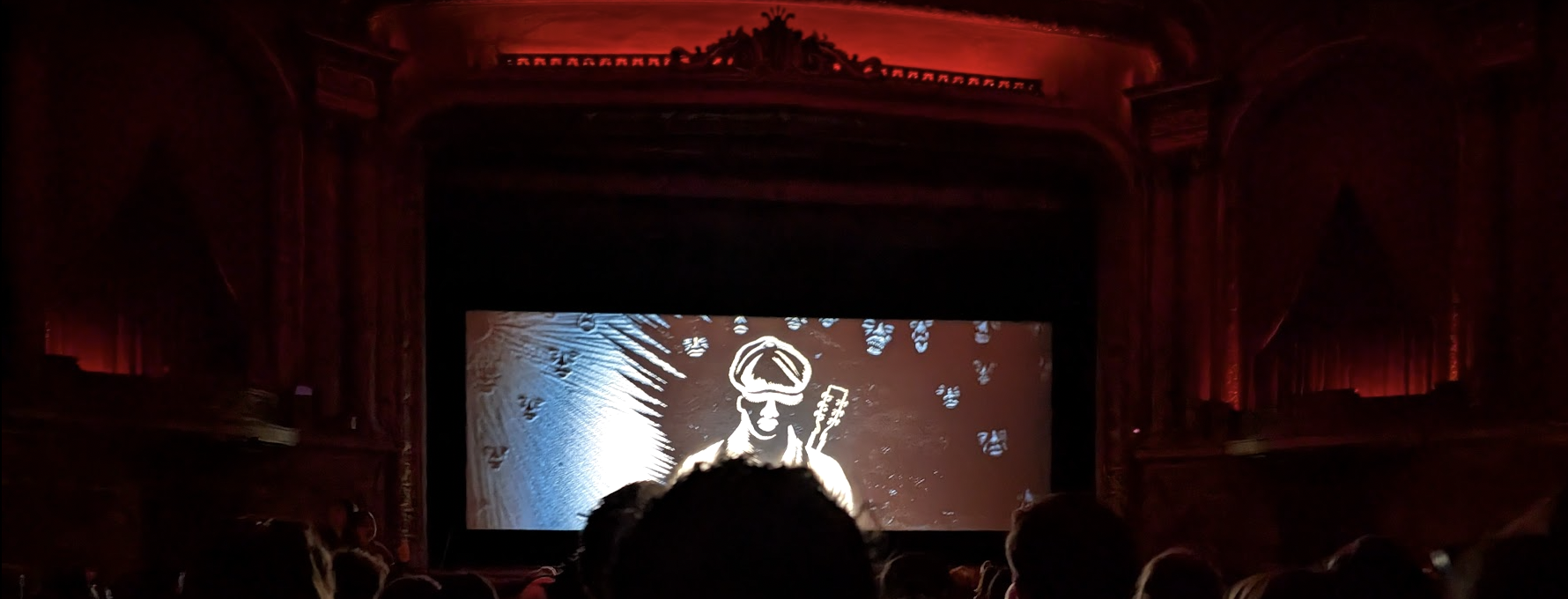

But take a step back from AIs: Coogler made Black Panther and then watched that get absorbed into the MCU's forever-ification of Wakanda. He took some old Oakland stories, a depth of pain and art and struggle, and it was absorbed into a vast and imperial MCU product that continued, that cursedly must continue, even after Chadwick Boseman died. And when you say “Black Panther,” now, what do people now associate it with? Do they think about the deep history of struggle embedded into Coogler’s hometown, that those words initially indexed, the actual Black Panthers? Or does it make people think about a Franchise owned by a big evil mouse, that has become an Intellectual Property, a Commodity, and a compelling surface without inner depth or meaning? It even becomes easy to forget what made Coogler’s Black Panther hit so hard in 2018; if you saw it with me at the Grand Lake Theater, then you would never question, for a second, whether it was great. But now, years later, after the MCU has done what it's done– and after, incidentally, Ryan Coogler produced a movie about betraying the Black Panthers–it’s a lot easier to say of his 2018 film: “this is a solid genre movie, but not great.”

Perhaps, if I follow the train of my own argument, you'd even be right. But what makes Sinners hit so hard for me, right now, is that it’s about the creative economy at a time when it feels so hard to make art for YOUR people, in a contextually appropriate time and place, out of your and your people’s pain and struggle. Even if you do that—say, if you make Fruitvale Station—you can still wake up one day and find yourself doing CGI with Kevin Feige. And then you find yourself losing individual control, or the ability to say “this is done”; you will find the thing you made absorbed into a totalizing omniconsciousness, endless and deathless, Wakanda Forever, whether you like it or not. You will find yourself thinking about the moment you said yes to it, the moment you invited it in the door.

In that sense, Sinners’s vampires are the MCU, but they're also all the tech freaks who used to live on the wrong side of the bay from Oakland that want to upload their consciousness into the cloud, give their brains to LLMs, and live forever together in and as one big social computer (so many of whom have, in the last decade, found their way into the Town). They’re why Buddy Guy, at the end, says that he's lived long enough, which is the movie’s statement on what art needs to be real and powerful: an ending. And it’s why the movie is called Sinners, in a way: If Capital says “Go forever! Never die! Never be satisfied!” as the goal of life—in a movie which is a standalone, will have no sequels, and simply satisfies you and then is over—you know who else tells you to live forever and never die? The opening scene of the movie suggests the artist will rejoin the church and put away art; note, in the end, that he has not and did not, at the peril of his immortal soul.

You might argue that what makes Sinners only good and not great is that it's an ungainly and overstuffed bag of too much, that the way it becomes impossible to summarize or reduce down into one thing, is also a lack of focus and clarity, and the component parts clash. Maybe so! Maybe in 2026, you're even right. But in times of excess and surplus, minimalism is a relief, and the reverse is also the case in our moment when far fewer movies are made, most of them the same, and when entire categories of once-thriving films are basically defunct. In 2025, it was incredible to see a movie that just said fuck it and did all the kinds of movie at once. Austerity capitalism gets rid of redundancies and excess and all the lavish extra-ness that this movie revels in; in that context, it was miraculous to see a movie that puts so many hats on top of hats, and that was the context in which we saw it, in which was made.

Artists don’t necessarily always know what they were doing when they make art, nor do they always, or often, tell the press what they know; they sometimes are even wrong about the thing they’ve made. I don't think Coogler exactly set out to make a Movie About Capitalism, and not only because he has said he didn’t; after all, Coogler has told the press that he thinks Wakanda Forever is good, which it is not. But there are two ways to theorize capitalism: One is to read Marx, but the other is to work for a living. I think Coogler—who has worked for a living—made a movie about how capitalism kills and eats culture, and also LLMs, and also about working for a living for parasitic studio vampires. I think that because I watched Sinners, a really great movie that is better than One Battle After Another, or whatever movie you liked more last year, and were wrong to do so.