I live in Oakland and work at San Francisco State University, an institution that might be identified in this publication as West Bay State University, a term I’ve always taken to index that The City is no longer the center of the region. But of all San Francisco institutions, SFSU is perhaps the least deserving of that decentering. After all, the campus has been an important place for student activism for decades, most famously the Black Student Union’s and Third World Liberation Front’s demands for relevant education (during what remains the longest student-led strike in history), which led to the first College of Ethnic Studies in the U.S. Of course, these days the university increasingly participates in the rise of technofascism through the Cal State system’s multimillion dollar partnership with OpenAI, while the College of Ethnic Studies has been starving.

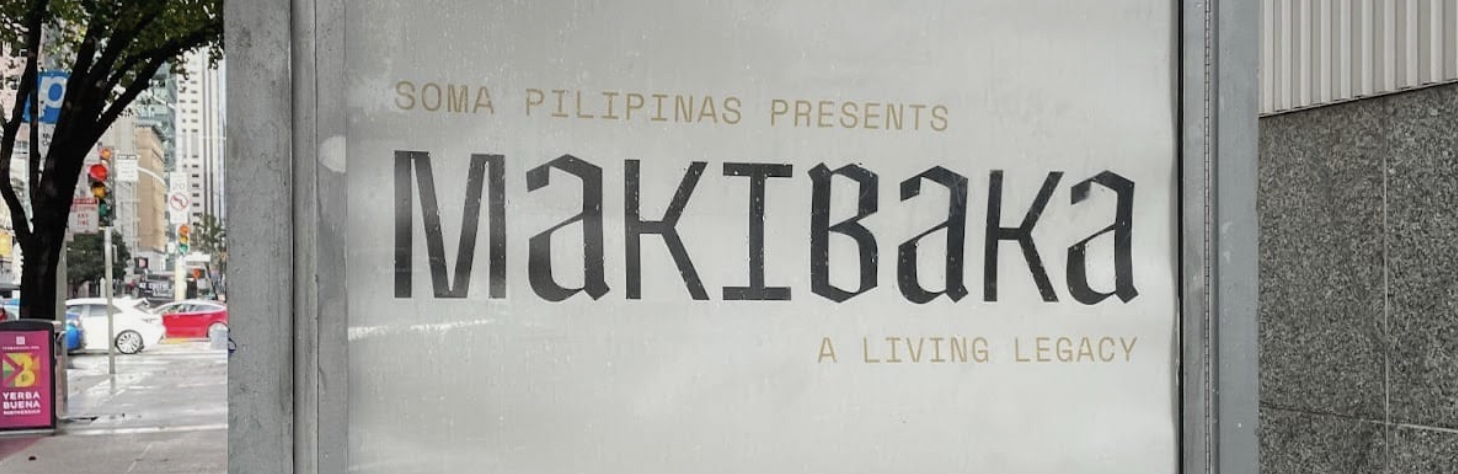

Anyway, I found myself reconsidering “West Bay” this past weekend, while visiting the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts for the closing day of Makibaka, an exhibition about the Filipino communities of SoMa. It was my second visit–the first was in September, when YBCA hosted a fireside chat with filmmaker and scholar Celine Parreñas Shimizu for a rare screening of her 1997 short film SUPER FLIP–and I had just returned from a holiday visit to my partner’s hometown of Brooklyn, where the only lick of Tagalog I heard during the entire trip was going through security at SFO. I had already planned to visit Makibaka again; as a Fil-Am (born and raised in South Florida), perhaps I knew that spending the start of winter in New York City would make me doubly homesick.

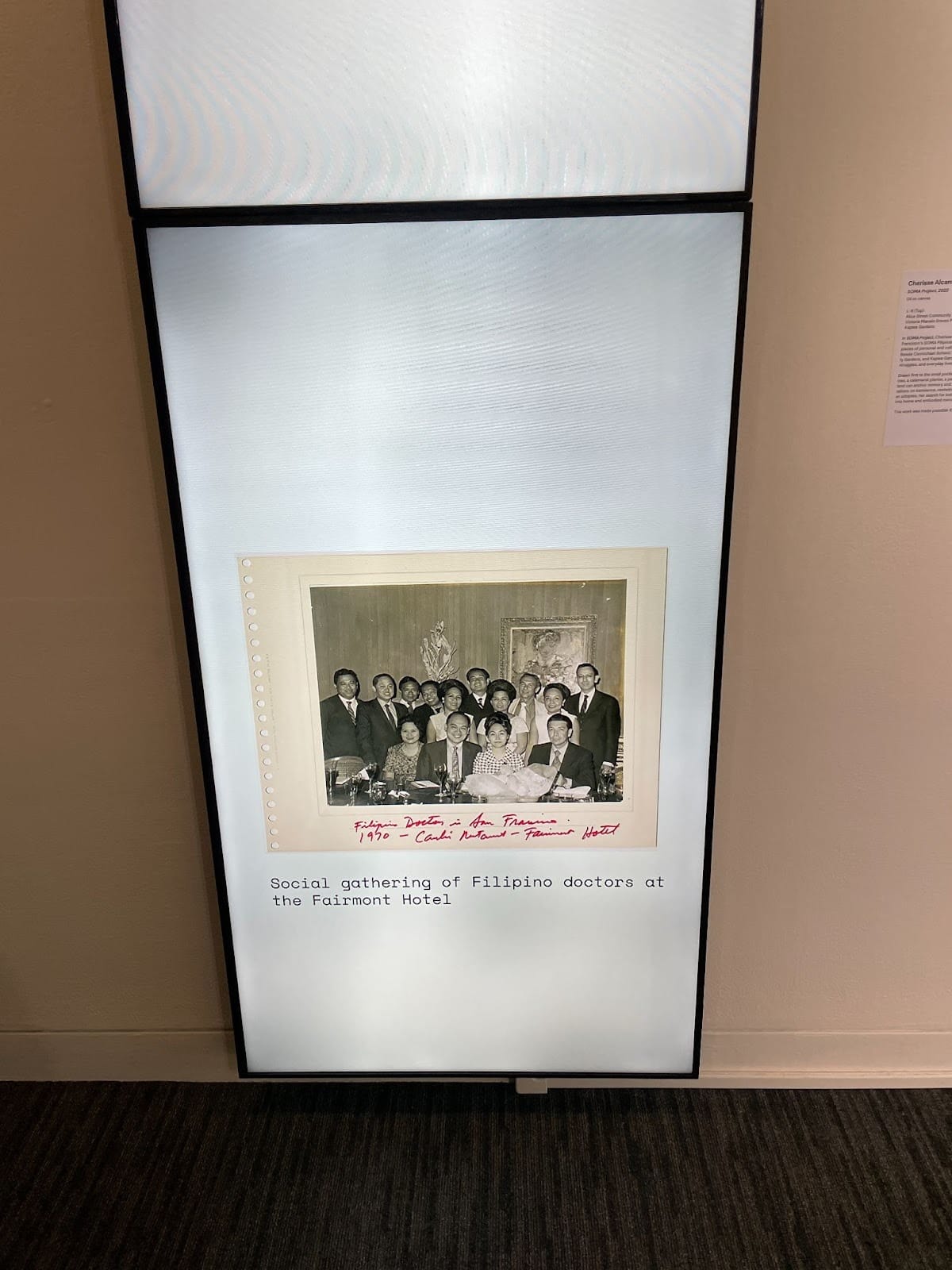

The exhibition emphasizes that the neighborhood’s Filipino history is not something of the past: The full title is “A Living Legacy,” and wall text bookending a timeline announces that the contents of the galleries are not about a “moment” but rather a “movement,” one that continues. After ascending the stairs inside YBCA up to the exhibition and taking in Cherisse Alcantara’s colorful visual odes to SoMa, I noticed two vertical flat screen televisions quickly rotating through photographs, with images that felt like looking through an extensive family photo album. From 1970: a picture captioned “Social gathering of Filipino doctors at the Fairmont Hotel.” Undated, but likely from the 1990s: a photo of three young men with slickly styled hair captioned “Eusebio and two friends at Mission High School dance.”

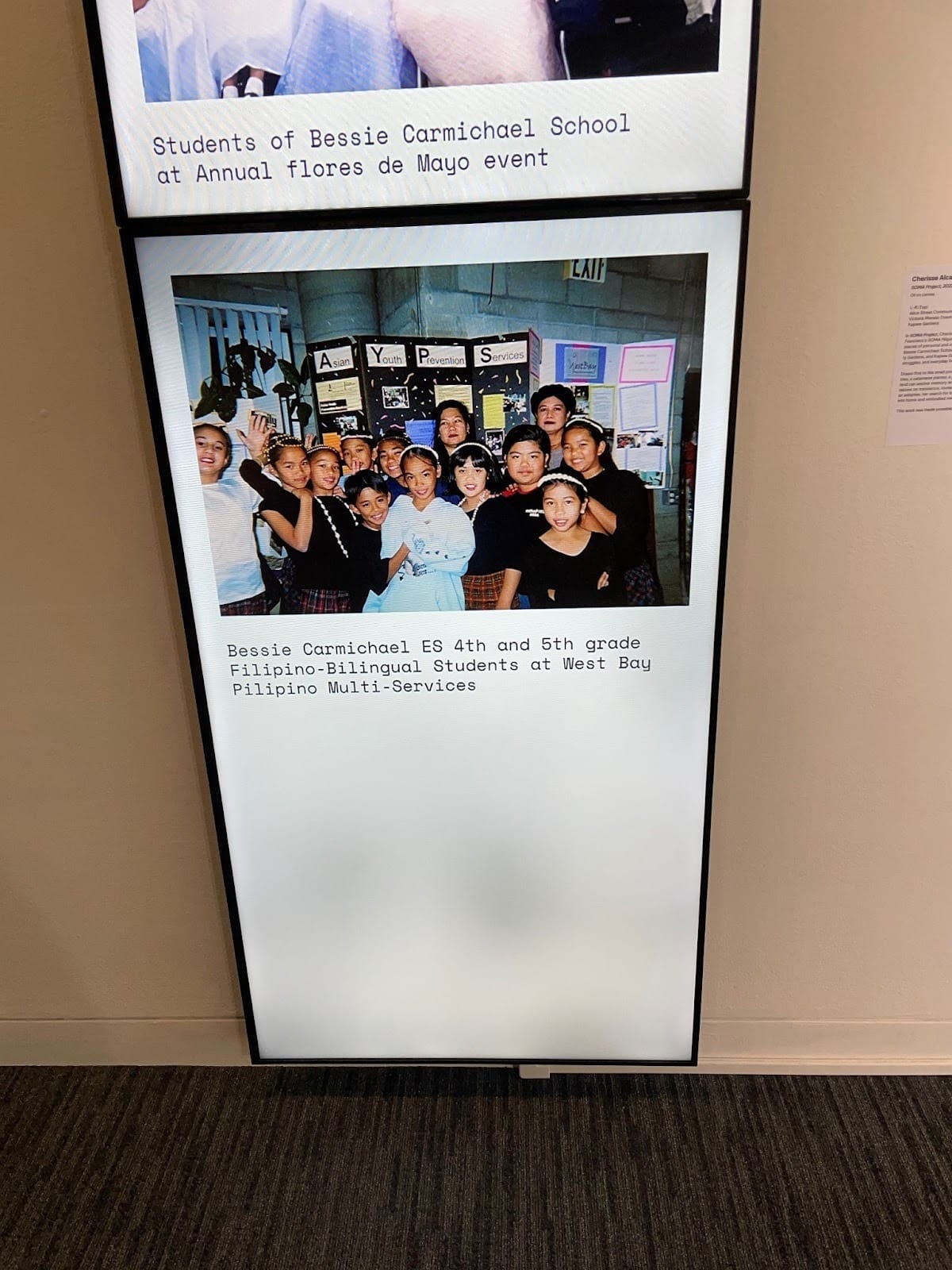

Then: a photo of fourth and fifth graders participating in Bessie Carmichael Elementary School’s bilingual education program at West Bay Pilipino Multi-Services.

I paused. West Bay? I was only familiar with the term through ORB. Yet here it was in this slide show celebrating the longstanding and quotidian presence of Filipinos in San Francisco. In fact, the moniker appeared multiple times in the slide show. I put “West Bay Pilipino Multi-Services” into a search engine and learned that the non-profit was established in 1968 after the consolidation of multiple community services for Filipinos. (Though it has existed for decades, West Bay Pilipino Multi-Services’s permanent home only opened in 2023.)

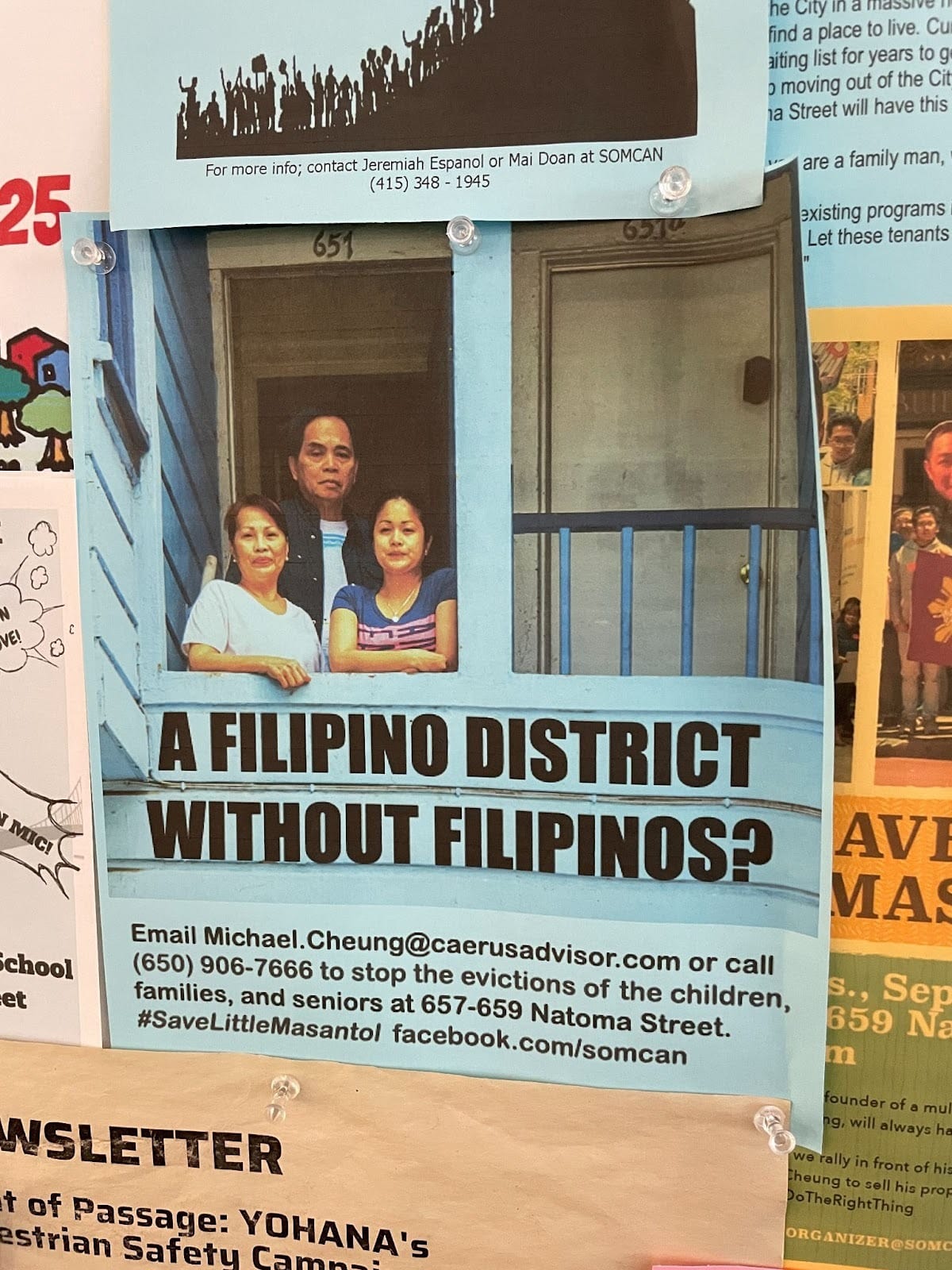

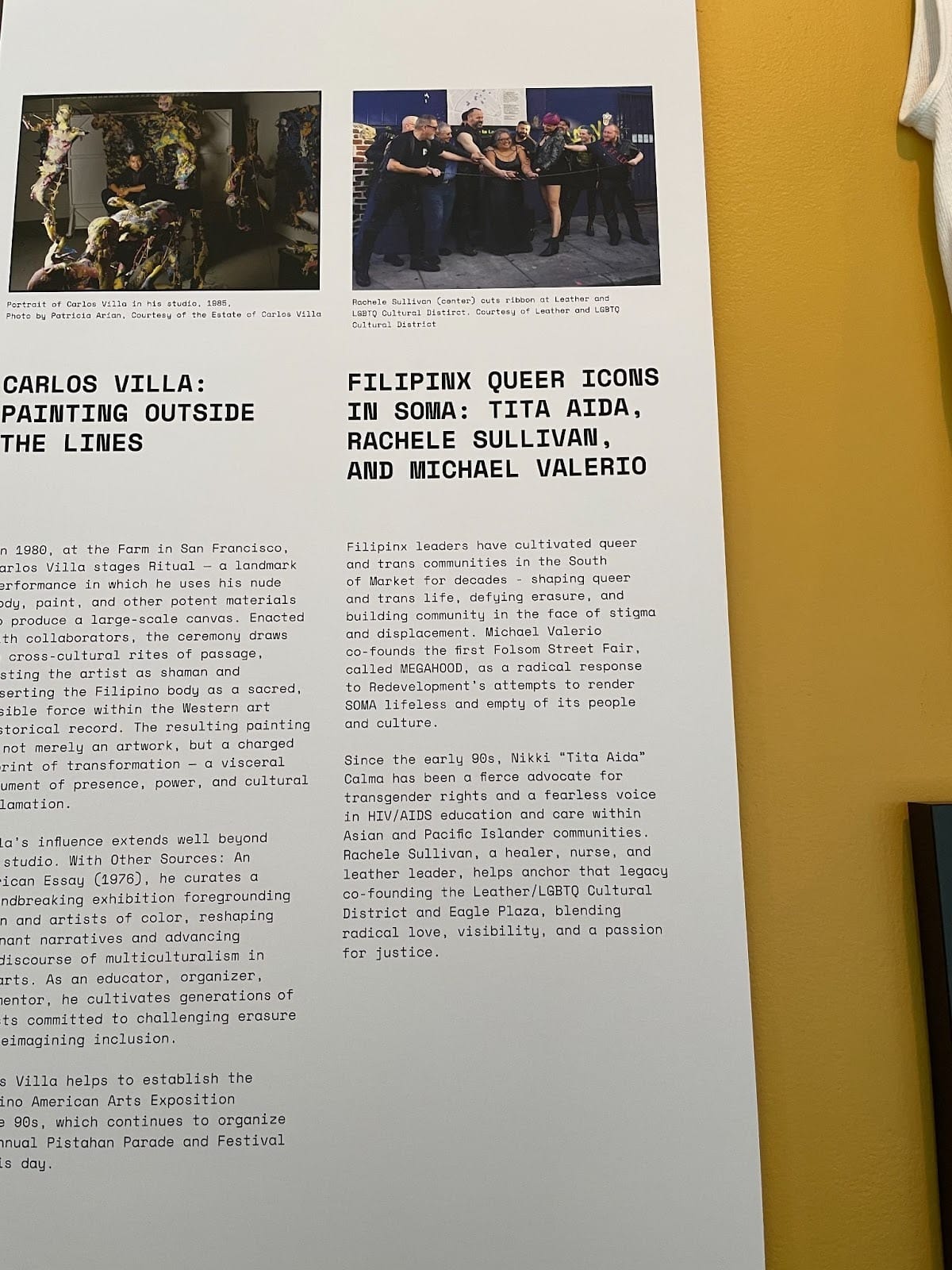

Perhaps you’ve heard of San Francisco’s Manilatown. Maybe at some point you’ve learned about the start of gentrification in San Francisco (well before the initial tech boom) and the eviction struggle at the I-Hotel and how this period galvanized the Asian American activism movement in the Bay Area. Makibaka spotlights these still little-known Filipino histories–but also even lesser known ones. For example, I learned that what has become San Francisco’s famous kink event–the Folsom Street Fair–started as Megahood, a street festival co-organized by a Filipino affordable housing advocate named Michael Valerio.

Visiting Makibaka ultimately made me feel less ambivalent about ORB’s insistence on identifying San Francisco as the West Bay. If a non-profit in San Francisco has been using the name for decades, perhaps the lesson is that Filipinos are among the Bay Area’s earliest counterprogrammers.