When this fine-looking young man in his late twenties, fresh from Nevada, lived in “San Francisco”—the name he had coined for the West Bay, which would actually become quite a fashionable way to reference the city—he didn’t spend much time in Oakland, which was also the style at the time: with a population of 1,543 in 1860, the there whose absence Gertrude Stein would eventually return to lament simply hadn’t yet arrived. The terminus of the Transatlantic railroad would only get there in the late sixties, after Clemens had already left.

And so, for him, Oakland is mostly a place to get away to, from San Francisco. It's not even particularly notable among the list of excursion destinations he mentions in a letter to his mother and sister: “We take trips across the Bay to Oakland, and down to San Leandro, and Alameda, and those places,” he writes, “and we go out to the Willows, and Hayes Park, and Fort Point, and up to Benicia.” Elsewhere, in a newspaper column called “Those Blasted Children,” he once referenced “goin’ across the bay to Oakland, ’n’ down to Santa Clara, ’n’ Alamedy, ’n’ San Leandro.” In his Autobiography, he once mentions someone who lived in “Oakland, or one of those suburbs.” (Ouch!)

In his travel memoir, Roughing It, he manages to mention Oakland just a bit more specifically, as a place you can get away to, from the West Bay wind: “you can go over to Oakland, if you choose—three or four miles away—it does not blow there.” (No air there?) Ironically, despite how often you hear the “coldest winter” joke attributed to Twain, he calls San Francisco weather “mild and singularly equable…as pleasant a climate as could well be contrived, take it all around” (albeit “the most unvarying in the whole world”). Oakland comes into focus, in that context, as a place whose weather is even more nothing-y than that.

Roughing It also contains an account of Clemens’ first earthquake, complete with a joke about “an Oakland minister” who responds to the quake with “Keep your seats! There is no better place to die than this,” until a moment later he thinks better of it, adding “But outside is good enough!” and skips out the back door. That the minister is specifically from Oakland might add a little spice to the joke, giving him a bit of a provincial, country air? Bernard Taper's gloss—in Mark Twain’s San Francisco—is that “Oakland had already begun to fulfill its divine destiny as the butt of San Franciscans’ jokes.” But I don’t know. If Oakland was a place to make fun of, Clemens wouldn’t have missed the opportunity so comprehensively throughout all of the rest of his work. I suspect Oakland wasn’t important enough to make fun of, and the minister was being described as being from there, simply, because he was.

After that, it gets pretty sparse. In an “Answers to Correspondents” column, he responds to "AMBITIOUS LEARNER" (who writes him from Oakland): “Yes; you are right—America was not discovered by Alexander Selkirk.” It is possible that this is a really good joke; the gag is that the questions the column is answering are not included, so you have to deduce what he’s responding to (either that or something about Alexander Selkirk is quite funny in this context). I can’t be bothered. Similarly, he references a form sent by “Oakland hospital people” in an essay he wrote “On the Decay of the Art of Lying,”for a contest, which he notes he did not win. In “Christian Spectator,” a column from 1865, he mentions “Oakland Female Seminary” and doesn’t seem to mean much by it. He once gave a lecture (“Woman—Mark Twain’s Opinion of Her”) and the Mark Twain Project archives produces a letter in which he mentions that “I lectured in Oakland the other night—guest of J. Ross Browne & his charming family, & a Mrs. Porter was to have been there to see me, but it rained & she couldn’t.”

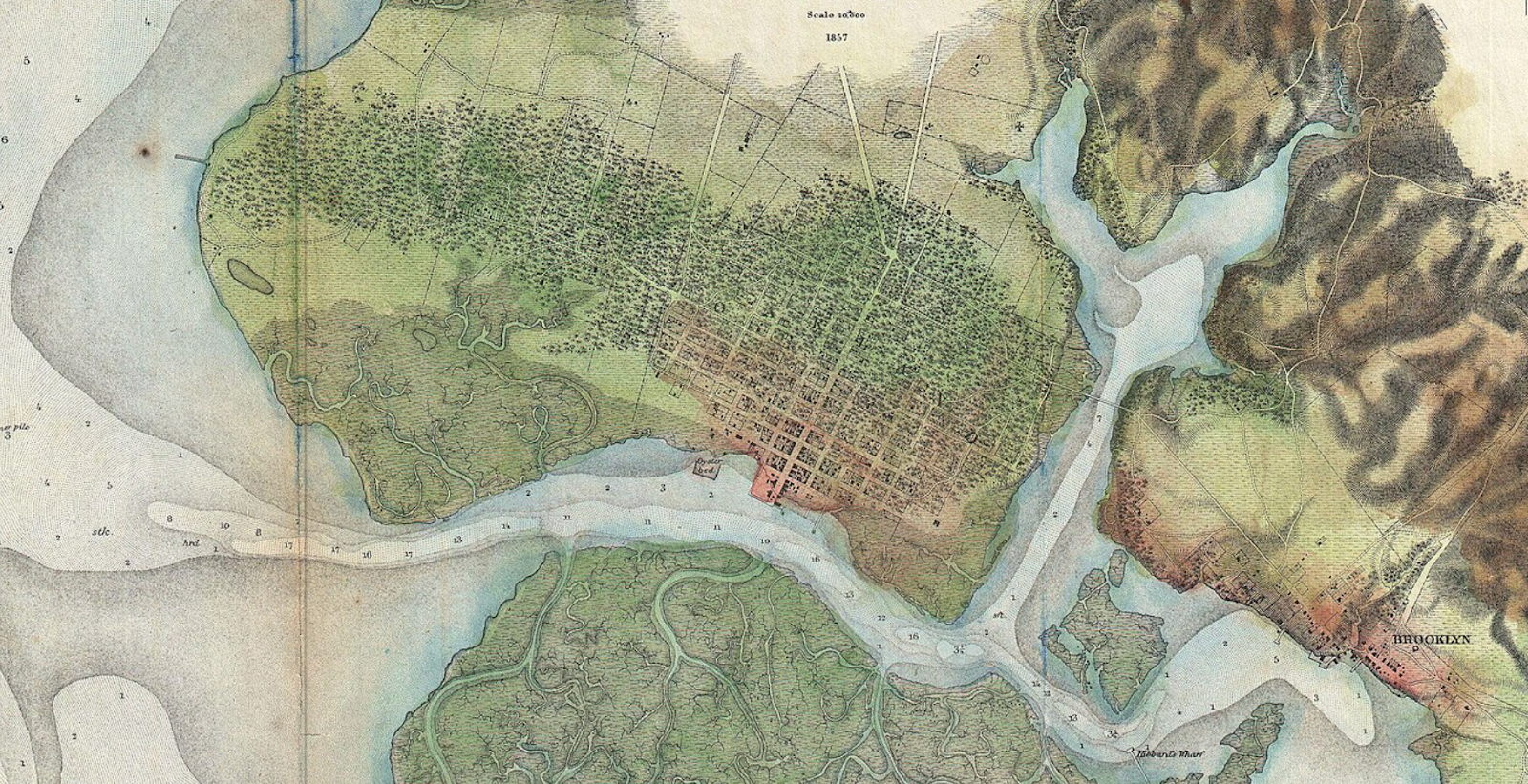

That’s basically the end of it. There’s a letter replying to a correspondent, then mining a claim in Nevada, who had apparently expressed some hope of moving to Oakland. Twain is doubtful. “You hope to go to Oakland!” he writes. “But I begin to believe that if you owned a Bonanza you would rot away there in Virginia City and never leave.” Oakland, here—beyond the random place that his friend happens to hope to retire to—seems a general place one might retire to, in California, “and be content to be comfortable.” A friend of his seems to have also ended up in Oakland; in his extremely posthumous Autobiography, he recalls an acquaintance who “built a little house in Oakland—ostensibly a house, but really it was a ship, and had all a ship’s appointments, binnacle, scuppers, and everything else—and there he and his little wife lived an ideal life during the intervals that intervened between his voyages.” When the autobiography was written, that part of Oakland had been annexed from what had been “Brooklyn,” and he refers to it as “Brooklyn, East Oakland” at one point, which is itself a nice way to crystalize how differently the Town was shaped back then. You can see in this map from 1857, how much sense Brooklyn makes as a place for a ship’s captain to settle (and why the Coast Guard island is located right there).

There is one other thing I came across, which Twain did not write about, as far as I can be bothered to know. He gave some kind of amusing speech in Oakland, in April of 1868—during a brief return to the Bay, after his Innocents Abroad tour had ended his proper residency in the city—and there was to have been a special ferry to Alameda, “leaving the wharf on this side at 6 o’clock, and returning at 11.” As his friend James F. Bowman, the editor for Oakland News, reported in an article called “Mark Twain Lost”:

Yesterday afternoon, about four o’clock, Mark Twain might have been seen rushing madly about in the neighborhood of the Oakland and Alameda ferry landings, on the San Francisco side, inquiring in a bewildered manner of all whom he met, “which boat he ought to take in order to get to the place where the dinner is to come off?” “What dinner?” inquired a benevolent looking citizen, who seemed to think that something was the matter with the pilgrim from the Holy Land. “Well,” responded Mark, with a bewildered look, “that’s the question. I agreed yesterday, or the day before, or the day before that, or some time or other, to go somewhere to a dinner that was to come off to-day, or maybe to-morrow, or perhaps to-morrow night, at some d—m place across the Bay. I don’t know exactly where it is, or when it is, or who I agreed with. All I know is, I’m advertised in the newspapers to be somewhere, some time or other this week, to dine, or lecture, or something or other—and I want to find out where the d—l it is, and how to get there.”