I am not a conspiracy theorist, but I sympathize. What right do I have to mock people trying to build communities dedicated to making sense of a confusing world? If their commitment to truth and justice is earnest, who cares if their amateur’s analysis is less rigorous than what I’d demand from a sociology professor or a professional journalist? As I took a bus from work to the 9/11 Truth Film Festival at the Grand Lake Theater on Thursday, I privately coached myself into adopting an open mind, or at least an open heart. I’m not sure if I was successful.

When I arrive and scan through the program, I am surprised to learn that most of the films released within the past year were screened hours ago. Why did they start the festival before five on a workday? Don’t these people have jobs? Apparently not; as I soon realize, the overwhelming majority of attendees are men deep into their retirement years.

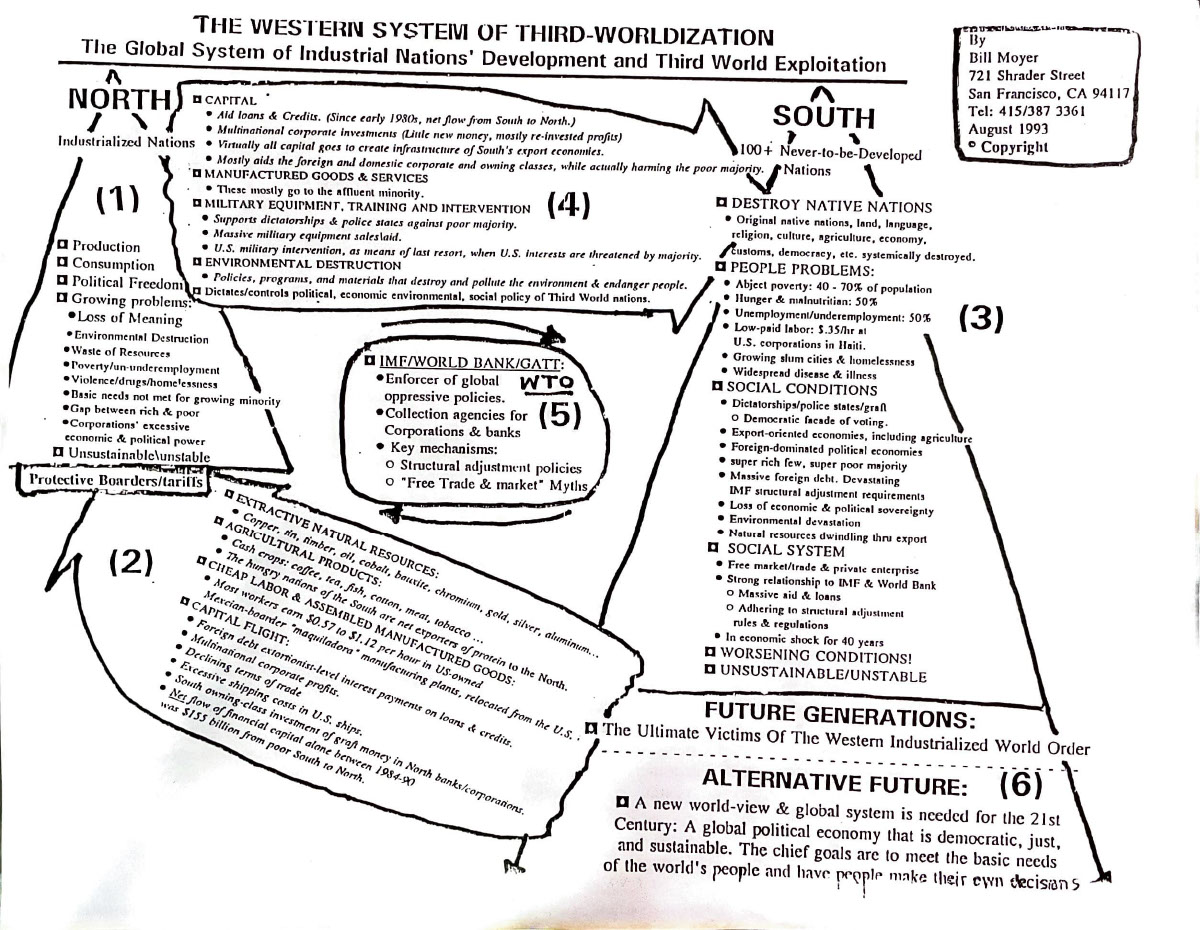

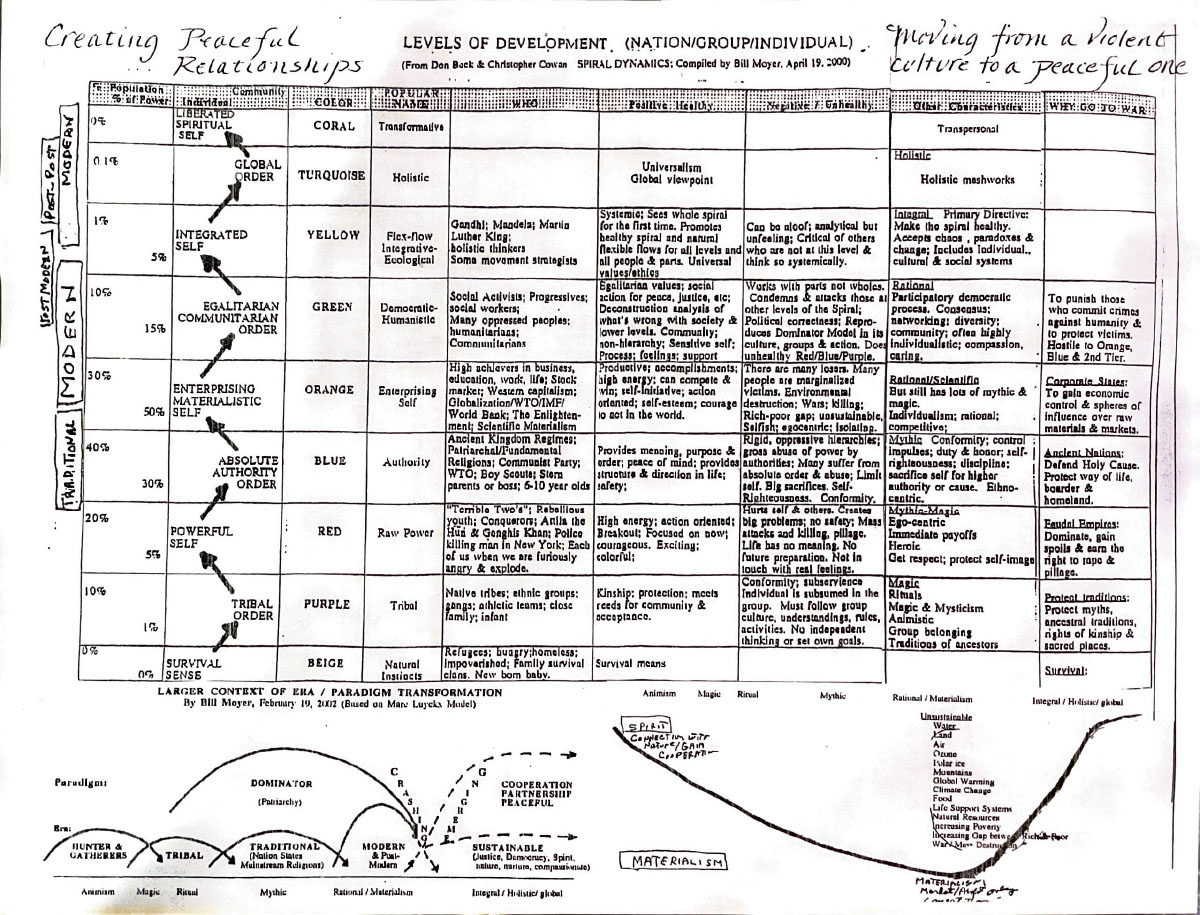

The lobby feels like a time capsule from 2007: vendors selling bumper stickers showcasing a dizzying variety of iterations on the phrase “9/11 was an inside job,” DVDs and CDs promising “explosive evidence” of a coverup, and even those novelty fake dollar bills with unflattering portraits of George W. Bush and Dick Cheney. But although almost everything on display was produced during the Obama administration (or even before 9/11 itself; some of the most interesting fliers were made in 2000 or even the early 90s!), my eyes are drawn to an impressively 3D-printed model of the skyline around Ground Zero before and after the towers collapsed.

The man behind the table is friendly when I ask, but his answers are vague, almost evasive. My N95 might be the problem. It outs me as a normie, and several attendees have already (gently) encouraged me to put it away. I do not. If I got covid at a 9/11 film festival, the embarrassment alone would kill me.

I do pull my mask down, momentarily, when I am invited to help myself to a complimentary 9/11 cookie from the refreshments table.

The films and speakers switch back and forth between two painfully boring forms of address. The first reminds us, repeatedly, that the official government reports on 9/11 are lies: fire, as you may have heard, cannot melt steel beams. We are shown a parade of slides, each of which cuts away long before you can finish reading the text. After an hour of this I realize that the point isn’t to read them, but the feeling you get—like serious, hard-nosed detectives—watching dry slides and technical diagrams. Besides, everyone here already knows what the slides say; they’ve been reading the same documents and making the same arguments for twenty-four years. The audience sits and nods in contented silence.

The scene becomes livelier during the second mode of address, which reminds us that propaganda is bad but truth is good. The crowd hoots and hollers to a clip of Jordan Peterson sputtering aimlessly about truth being objective. We see a TEDx speaker yell “We want the truth! We want the facts!” to a jubilant auditorium that is far more crowded than this one. A retired Seattle fire captain named Raul Angulo takes the stage and delivers a rousing address about his path to the movement. When he yells “I am proud to be a truther and a conspiracy theorist!” the crowd erupts.

People here are touchy about the second term. If they embrace it, they’re plainly bitter about its use by those outside this community. The odd thing is that I don’t see much theorizing about any specific conspiracies here. Everyone takes pleasure in agreeing that there was a coverup, but there is no consensus on who the criminals are. During an intermission I speak with Roger, one of the many polite elderly gentlemen in the lobby. After describing his plan to replace the United Nations with something called the Earth Federation, he asks me if the next film is going to actually name the actual criminals behind 9/11. I shrug and ask him who he thinks masterminded it. He mutters something I don’t quite catch about Mossad and excuses himself to buy a hot dog.

The sense of shared community purpose also runs aground a little on more conventional politics. There’s tension in the room when Capt. Angulo starts to talk about the future; “The reality is that I see a lot of older people here,” he avers. “We may not live long enough to see everything we are working for come to fruition. How do we avoid falling into despair?” His answer is fairly clear: converting to Christianity, like his acquaintance Charlie Kirk who had been assassinated the day before. “Charlie Kirk was good Christian!” he booms.

The audience is split. Some cheer, including (to my surprise) an older man near me wearing a shirt that reads, “got science?” But there is loud dissent from the handful of young members of the audience. (“No he wasn’t!” “Fuck that guy!”) At the end of Angulo’s sermon I remain seated and listen to the audience walk back to the lobby. A man in his twenties is talking to his friends: “He was doing so good until he was on that ‘Charlie Kirk was a good person’ bit. Like, are you out of your fucking mind?!”

The psychology of denial is a recurring theme in the films and talks. Angulo describes his previous hesitancy to become a Truther as a form of cognitive dissonance: “First you reject it [the truth about 9/11]. Then you get angry. Then you discredit the speaker, you call them whackadoodles. I did it all.”

My experience was different. An hour into a documentary about Tower 7 (the third tower to fall at ground zero), in the middle of an extended section on a specific steel pillar on a the seventeenth floor, I found myself suddenly willing to believe all of it just so I could stop thinking about this shit. Yes, Tower 7 was destroyed by explosives, fires cannot melt steel, whatever you say, just don’t make me look at another fucking slide.

My serotonin levels cratering, I retire to the lobby once again and buy more milk duds.

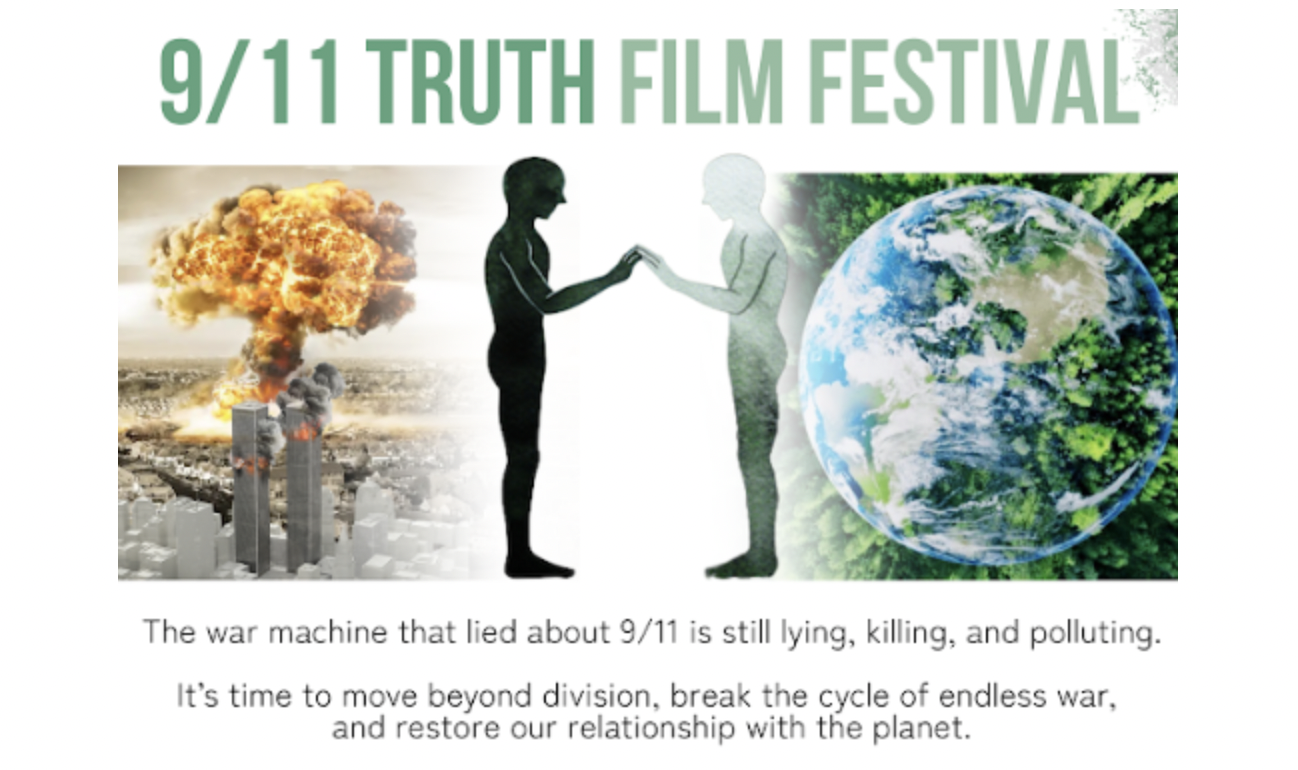

To my surprise this year’s festival has a vague environmental theme, and is even dedicated to a recently-deceased deep ecologist. Their website asks “What kind of future do we want? The war machine that lied about 9/11 is still lying, killing and polluting. We believe a brighter future is possible. It's time to move beyond division, break the cycle of endless war, and restore our relationship with the planet.”

It’s clear that the event’s organizers recognize that their movement is in a bit of a rut, and are searching for a way out. The titles of the entries earlier in the program carry more of a hippie vibe (e.g. Why The World Needs You To Feel Again), which is in keeping with the florid ecological aesthetic of the official event poster and, frankly, the demographics of most of the people here.

Of course, the paradox is that their entire community is innately rooted in the events of the past. To move forward from 9/11 itself would jettison their only true point of ideological unity.

The final film of the festival begins with a cascade of dramatic stock footage and what seem like Batman quotes: “The criminal scrambles to cover his tracks” flashes on screen over a burst of flames. Suddenly a man in the audience runs to the middle of the aisle and waves his hands in the dark; “I forgot I was supposed to introduce this film!” He is yelling an improvised introduction over the film’s actual opening sequences, and though I can barely understand any of it, both canceling each other out, he appears to be saying something about dark forces gathering in this country.

I can agree with that much. I take a final swig of my root beer and decide to go home. As my bus pulls up, I keep thinking about the resigned tone of one of the announcements during an intermission: “I encourage you all to donate to support the efforts of the people who organized this. Just give until it hurts. Any extra funds will help cover costs for the next festival. I... I assume we’ll all be here again next year.”